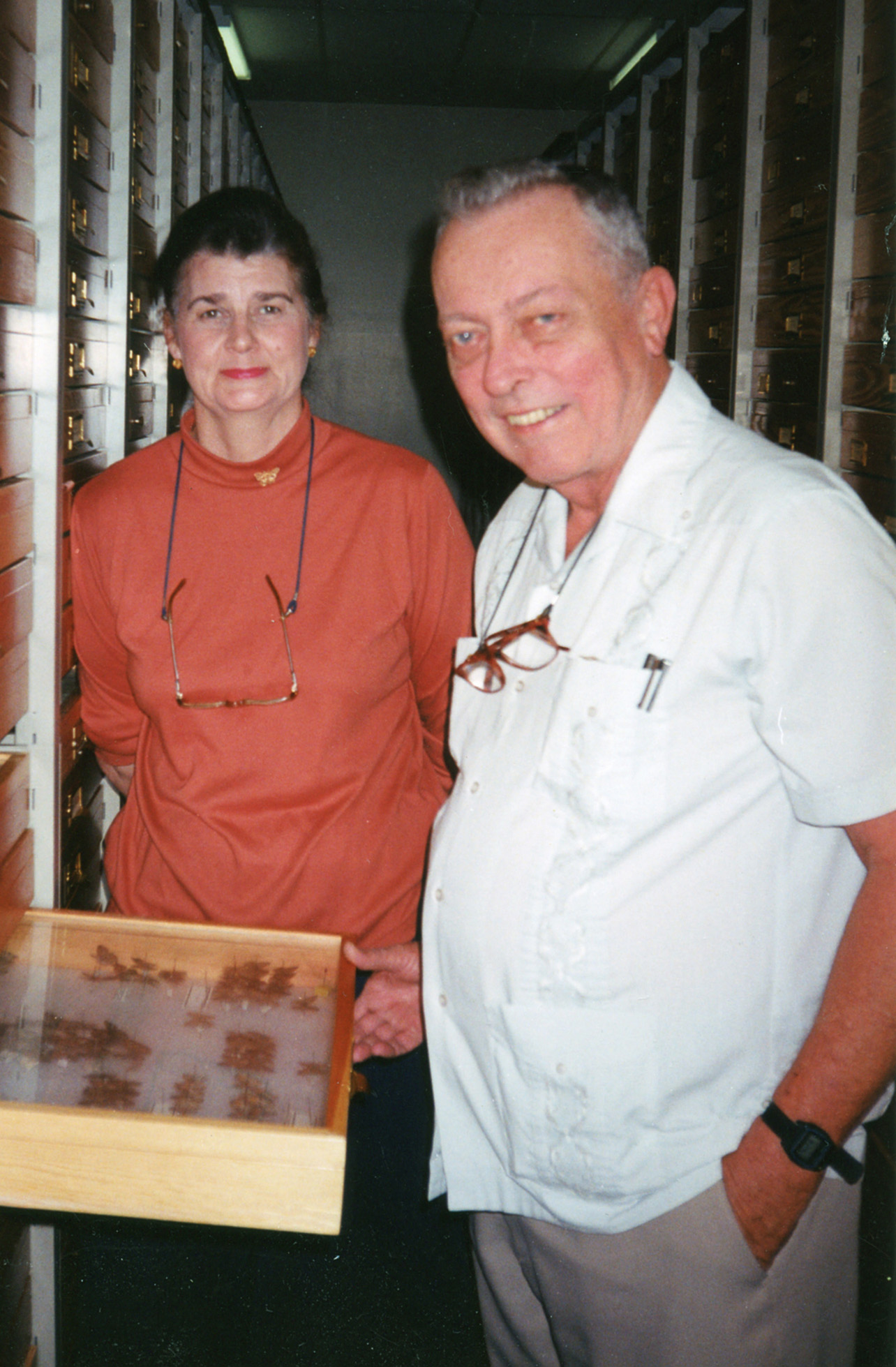

Jacqueline Miller, Allyn curator emerita at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity at the Florida Museum of Natural History, passed away peacefully earlier this year on July 8. Jacqueline and her husband, Lee Miller, were among the most influential and respected lepidopterists of their time. Together, they co-authored dozens of peer-reviewed studies, collaborated on books and were active members of several scientific societies.

“Neither of us could deny the natural compatibility and magic behind what would become the ‘Miller team,’” Jacqueline wrote in an article commemorating Lee after he died in 2008.

Their magic extended to others as well. They both supported numerous students throughout their careers, despite working for several years at a private institution that had no official connections with schools or universities.

Yet somehow, budding lepidopterists seemed to have little trouble finding the Millers.

“The first time I met Jackie was on a road trip that my mother and I took to Florida when I was a teenager,” said James Adams, a biology professor at Dalton State College. At the time, Jacqueline and Lee Miller worked as curatorial staff members at a privately funded museum, named after its benefactor Arthur Allyn Jr., located in Sarasota, Florida. “I’ve always been interested in butterflies and moths for as long as I can remember, and I’d heard of the Allyn Museum. I thought I should drop in and see what’s going on, not realizing it wasn’t a public museum.”

The door was locked when Adams and his mother arrived, and the squat, imposing building had no windows along the side that they approached. He knocked anyway.

“Jackie opened the door, took us right in and showed us around,” he said.

This was typical of Jacqueline, known as Jackie to friends and colleagues. She effortlessly exerted a magnetism that pulled people in and kept them in her orbit.

Jaret Daniels, curator of Lepidoptera at the Florida Museum, recounted a similar first encounter with Jackie at a Lepidopterists’ Society meeting that he attended with his mom when he was in high school.

“The main memory I have of her from that meeting was being impressed that this experienced professional would take the time to talk to me about my interests and future goals,” Daniels said. “It was an incredibly formative experience in guiding the direction of my career.”

Jackie’s many accomplishments, awards and contributions to the field of Lepidoptera have been thoroughly documented in several articles and profiles. Her life and career were highlighted last year in American Entomologist. The Who’s Who of Professional Women outlined her significant milestones in 2018, and the News of the Lepidopterists’ Society newsletter ran profiles of both Jacqueline and Lee Miller when they separately served as president, from 1989-90 and 1983-84, respectively.

Rather than reiterate the content these articles have summarized so well, the following is a short account of the ways in which Jackie influenced the people around her and the impression she left behind.

Jacqueline Miller’s career, from urban warehouse to butterfly bank to jungle laboratory to largest U.S. Lepidoptera collection

The Millers spent the majority of their careers working at the Allyn Museum of Entomology and following it as it was uprooted from Chicago to Sarasota and then on to Gainesville, where it became the nucleus for collections at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity.

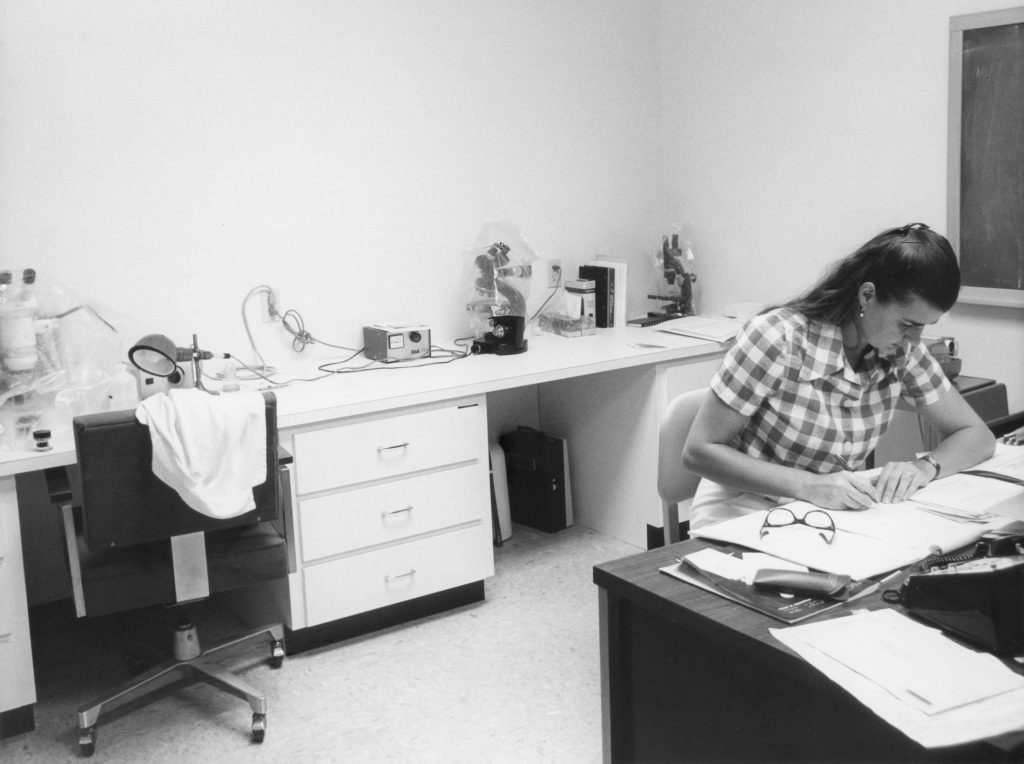

The museum was the passion project of Arthur Allyn Jr., a business executive with a soft spot for baseball and butterflies. In 1968, he pulled together a patchwork of various butterflies and moths he’d collected and purchased throughout his life and hired Lee and Jackie to curate it. At the time, the specimens were kept in boxes strewn across the floor of a warehouse in Chicago and in dire need of organization.

Allyn co-owned the Chicago White Sox with his brother, and each spring, the team would head down to a practice field in Sarasota, Florida, to avoid the cold. In 1969, Allyn decided to move there, taking the museum and the Millers with him. Jackie and Lee zealously added to the collections during this time, and within four years, the museum had outgrown the confines of the Sarasota Bank and Trust building, where it initially resided.

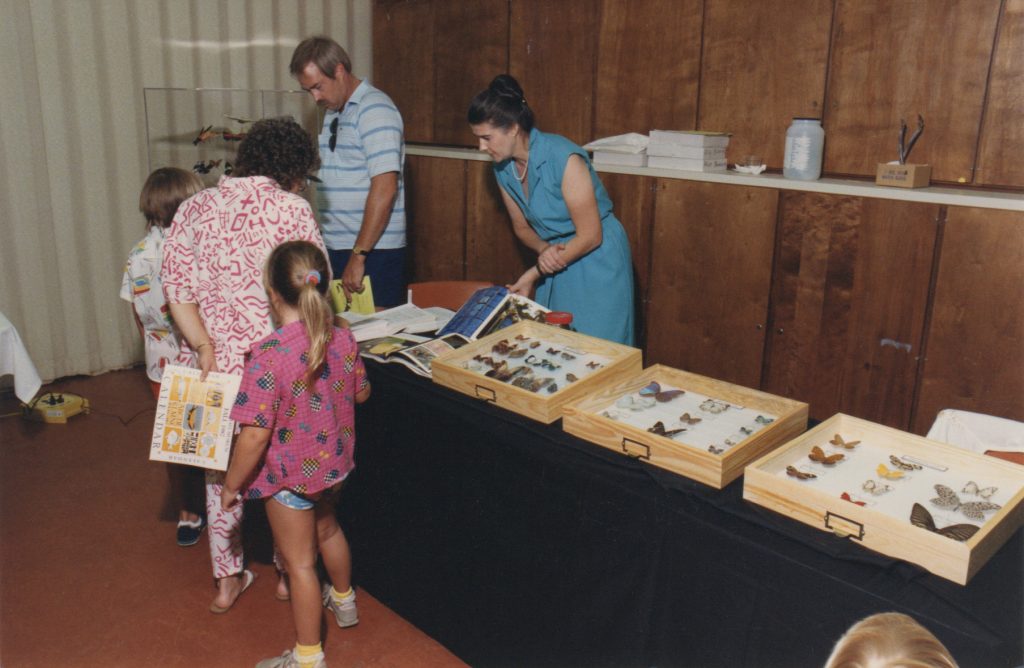

Allyn purchased the Sarasota Jungle Gardens and designed a new building with input from the Millers and had it constructed on the southeast corner of the property in 1973. With plenty of room, resources and what was quickly becoming a renowned collection, the museum was a hub for lepidopterist experts the world over.

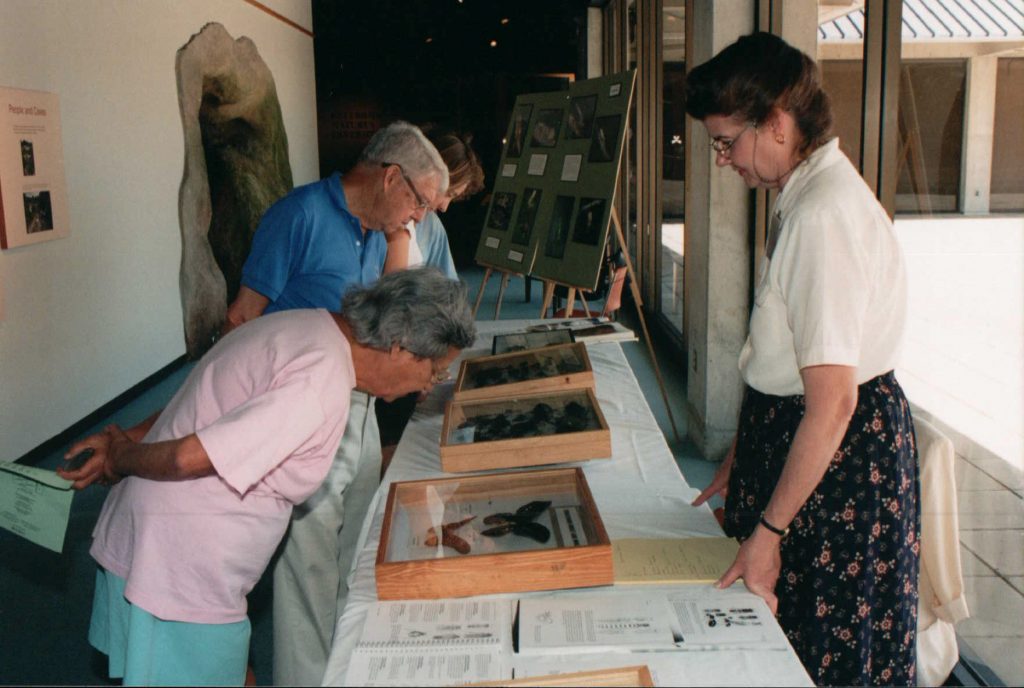

“They were very welcoming to researchers, and they’d host them in their home while they were staying and working at the museum,” said Deborah Matthews, a collection manager for Lepidoptera at the Florida Museum.

Like Adams and Daniels, Matthews met Jackie when she was a teenager and received similarly sincere and supportive treatment. At the time, her father ran a computer store in Sarasota and was contacted by Allyn, who was interested in purchasing a computer for the museum. Before meeting to discuss the best options, Matthews put together a ledger of her own personal butterfly collection to demonstrate how databases could be created electronically. Months later, when Jackie needed a computer to write her dissertation with, she reached out to Matthews’ father, remembering both his business and his daughter’s fascination with butterflies.

“They mentioned they were looking for volunteers to come work with them,” Matthews said. She was 16 at the time and leapt at the chance. Jackie mentored her through her early academic studies, and when it came time for graduate school, introduced her to a professor at the University of Florida who would become her adviser for her master’s degree.

Jackie and Lee taught as adjunct professors at New College for several years and learned to spot the students who were enthralled with insects.

“I took an entomology class and laboratory with Jackie and Lee, and it was a completely life-changing experience,” said Emily Heffernan, professor of biology and environmental studies at New College. Heffernan had just switched from majoring in linguistics and anthropology at a large research university to studying biology at the small liberal arts college in Sarasota. She began volunteering at the museum and studied the co-evolution of a native plant and its moth pollinator.

Later, Jackie co-advised Heffernan when she was a doctoral student at the University of Florida. “She always treated me as a scientist and a professional with real aspirations. She really set the tone for me and the arc of my career,” she said.

Photo by Mesene, CC BY-NC

Jackie, who had a master’s degree but not a doctorate when she was hired at the Allyn Museum, enrolled as a doctoral student at UF in 1982. For the next several years, she delicately balanced graduate courses and research for her dissertation with full-time work at the Allyn Museum. Though the two institutions were nearly 200 miles apart, she regularly made the journey back and forth. “I saw the sunrise many times on I-75 as I was driving from Sarasota to Gainesville. I really wondered whether I would make it or not,” she said in a 2023 interview, referencing her degree. “But then I thought, ‘What the hell. I put all this time into it. I’m going to finish.’”

Jackie did finish and was awarded her doctoral degree in 1986. Instead of pausing to rest, she began writing a book on the butterflies of the West Indies and South Florida. This spirited determination served her and others well throughout her career. Without intending to, she’d struck a vibrant note that resonated with her students.

“There were few female entomologists at the time, and it was a challenging world to navigate,” Heffernan said. “That’s something she was always very clear, firm and supportive of me in. She was a great role model for not demanding respect as a female scientist but earning it as a scientist of great reputation.”

When Allyn’s health began to decline in the late 1970s, he made the decision to transfer the collection to the Florida Museum of Natural History in 1981. It remained in Sarasota for the next 23 years and operated as an off-campus unit. Then, in 2004, the Millers followed the collection one last time when it made the move to University of Florida campus in Gainesville. By then, it had swelled to 1.2 million specimens.

“There are still drawers scattered throughout our collections in the original state to which they were curated by Jackie and Lee at the Allyn Museum, which we are continuing to integrate,” wrote Florida Museum Lepidoptera curator Keith Willmott in an email. “I am constantly impressed by the extraordinary efforts they put into building up that collection.”

Today, the McGuire Center holds more than 10 million moth and butterfly specimens, making it the nation’s largest Lepidoptera collection.

“Who would have ever thought we’d have a butterfly and moth [collection] here at the University of Florida,” Jackie said in a 2022 interview on her research with hawk moths. “I’m very happy we’ve been able to do this.”

Throughout their careers, Jackie and Lee conducted extensive field surveys to collect specimens. They worked in South Africa, Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil and Peru, and they had a special affinity for the Caribbean, where moths and butterflies still fluttered in scientific obscurity. They embarked on several trips over several decades, to Honduras, Cuba, Puerto Rico and several other islands in the Greater Antilles.

Jackie’s focus throughout was primarily fixed on butterfly moths, in the family Castniidae. As their name implies, moths in this family often have bright colors and extravagant patterns that give them the appearance of butterflies.

“She was fascinated by that,” Jorge González wrote in an email. González developed his own fascination for butterfly moths when he was a student and discovered Jackie’s work on the group through her husband. “Her dissertation is the most relevant contemporary work on the Castniidae. She helped me finish my undergraduate project on the Castniidae of Venezuela.”

Jackie continued to teach and mentor students at the University of Florida. She taught a variety of entomology courses, along with others on scientific illustration and a seminar on orchids, which she cultivated in her spare time. She also served as major adviser or committee member for 20 students throughout her career.

Montana Atwater worked on a project at the McGuire Center as an undergraduate, and when it came time for graduate school, Jackie offered to be her adviser. “I was honored to have the opportunity to study with her,” Atwater wrote in an email. “As an adviser, she could be firm and pragmatic in her support, but also allowed me the freedom to develop my own ideas as a researcher and my own path as a female scientist.”

Those who wish to make a donation in memory of Jackie may give to the Allyn/Miller Research and Collections Fund in support of curation and research at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity.