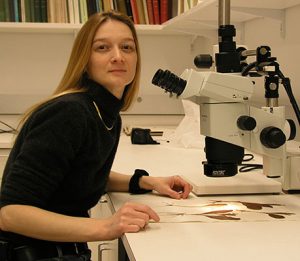

Nico Cellinese, assistant curator of the Florida Museum of Natural History herbarium and informatics, has received a prestigious $865,000 CAREER Award from the National Science Foundation.

Photo courtesy of Reed Beaman

The grant will support Cellinese’s research on genetic diversity in the flowering plant group Campanulaceae, also known as the bellflower family, in the Eastern Mediterranean Basin, especially on islands in the Aegean Sea. The five-year award totals $865,251 and begins March 1, 2010.

The plant sample she will study includes about 200 species confined to extremely localized places, said Cellinese, who is also a University of Florida assistant professor in biology. These endemic species raise interesting questions about their evolutionary origins and why they are found only on islands in the Aegean archipelago.

“I want to find out whether these islands essentially serve as evolutionary laboratories,” Cellinese said. “Either the islands have been generating new species since being separated from the mainland or the species found on the islands are leftover fragments of an older flora that extended to the mainland before going extinct there.”

The answer to that question will have implications for conservation planning, Cellinese said. The Aegean islands have undergone extreme pressure from human activities for thousands of years. Agriculture, grazing and tourism have significantly altered and reduced these species’ habitats. “Many of these species are threatened or endangered and are essentially at risk of extinction,” she said.

The Aegean Sea has nearly 100 islands, the largest of which is Crete. During an event 5.9 million years ago known as the Messinian Salinity Crisis, the Mediterranean Sea dried up as the Strait of Gibraltar closed access to the Atlantic Ocean.

The event greatly affected the region’s composition of plant and animal species. Areas that had been underwater were now open land, allowing for greater exchange of species in places that previously had been isolated. The Mediterranean basin eventually started to flood again about 5.3 million years ago.

Cellinese plans to begin collecting samples of the islands’ endemic species in May. The fieldwork will also involve collecting species found on the mainland of Greece, Turkey and the Balkans. Back in the lab, data collected on the species’ morphology and a set of genetic markers will be used to determine evolutionary relationships among the different lineages.

“The systematics of the group needs to be clarified, and in this work we’ll do that,” Cellinese said.

She will use part of the funding to hire one graduate student and one post-doctoral researcher. She also will develop two online courses in Mediterranean biogeography, one for graduate and undergraduate students and the other for K-12 students.

The project also has a technology-development component that would integrate existing analytic tools within a single database management system. This would allow scientists to conduct studies of phylogenetics, population genetics and statistical inferences in a more efficient research environment.

Visit the Cellinese Lab website.