Natural history museums have entered a new stage of scientific discovery and accessibility with the completion of openVertebrate (oVert), a six-year collaborative project among 18 institutions to create 3D reconstructions of vertebrate specimens and make them freely available online.

Researchers published a summary of the project in the journal BioScience in which they review the specimens that have been scanned to date and offer a glimpse of how the data might be used to ask new questions and spur the development of innovative technology.

“When people first collected these specimens, they had no idea what the future would hold for them,” said Edward Stanley, co-principal investigator of the oVert project and associate scientist at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Natural history museums got their start in the 16th century as cabinets of curiosity, in which a few wealthy individuals amassed rare and exotic specimens, which they kept mostly to themselves. Since then, museums have become a resource for the public, with exhibits that showcase biodiversity for anyone interested in learning about it.

However, the majority of museum collections remain behind closed doors, accessible only to scientists who must either travel to see them or ask that a small number of specimens be mailed on loan. The research team behind oVert wants to change that.

“If you require someone to get on a plane and travel to you to collaborate, that’s prohibitive in a lot of ways,” said David Blackburn, lead principal investigator of the oVert project and curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum. “Now we have scientists, teachers, students and artists around the world using these data remotely.”

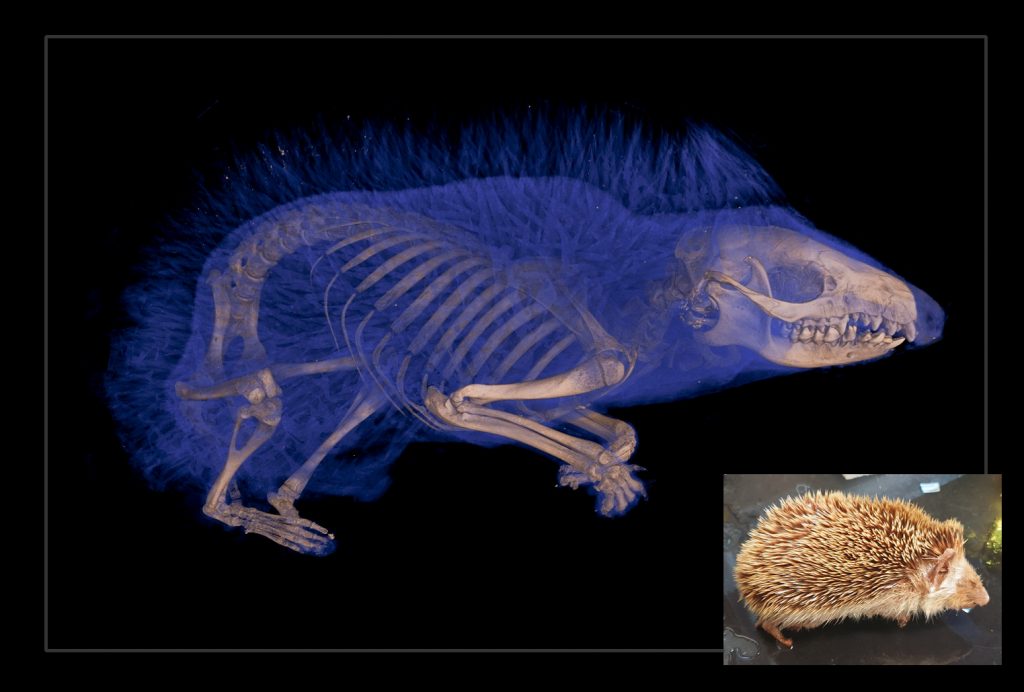

Florida Museum image by oVert

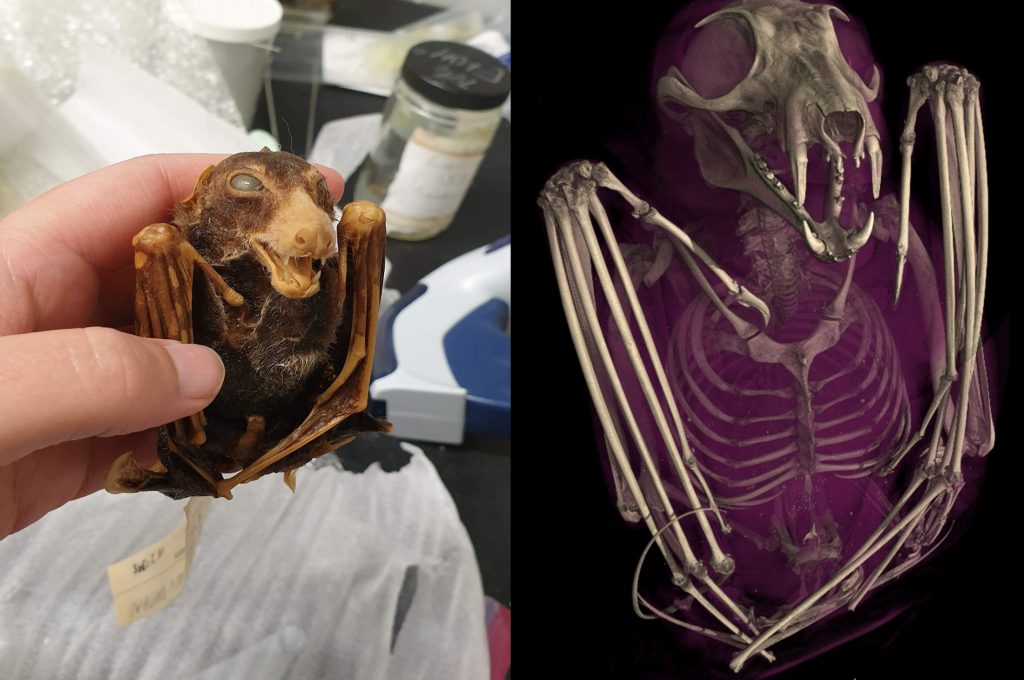

Between 2017 and 2023, oVert project members took CT scans of more than 13,000 specimens, with representative species across the vertebrate tree of life. This includes more than half the genera of all amphibians, reptiles, fishes and mammals. CT scanners use high-energy X-rays to peer past an organism’s exterior and view the dense bone structure beneath. Thus, skeletons make up the majority of oVert reconstructions. A small number of specimens were also stained with a temporary contrast-enhancing solution that allowed researchers to visualize soft tissues, such as skin, muscle and other organs.

The models give an intimate look at internal portions of a specimen that could previously only be observed through destructive dissection and tissue sampling.

Florida Museum image by oVert

“Museums are constantly engaged in a balancing act,” Blackburn said. “You want to protect specimens, but you also want to have people use them. oVert is a way of reducing the wear and tear on samples while also increasing access, and it’s the next logical step in the mission of museum collections.”

oVert was funded with an initial sum of $2.5 million from the National Science Foundation, along with eight additional partnering grants totaling $1.1 million that were used to expand the project’s scope. The goal was to initially scan only specimens preserved in ethyl alcohol, which represent the bulk of fish, reptile and amphibian collections. Specimens that are too large for fluid preservation are also unlikely to fit into a CT scanner, but researchers were reluctant to leave these out.

A partnering grant to the Idaho Museum of Natural History was used to create a digital model of a humpback whale. The entire specimen was too big to scan with sufficient resolution, so researchers painstakingly took apart the skeleton, produced 3D models of each individual bone, then reassembled the physical and digital specimen.

Even moderately sized specimens at times required a little ingenuity, as was the case with a set of iconic tortoises at the California Academy of Sciences.

“They have the largest Galapagos tortoise collection in the world. These are not things you put in boxes and loan,” Blackburn said.

Using funds from another partnering grant, curatorial staff members had to come up with a way to photograph each tortoise in a 360-degree rotation. Photographing their undersides was problematic, as their curved shells made it impossible to keep them upright. After a few trial-and-error runs, they settled on placing the specimens on top of inflatable swimming tubes.

Scientists have already used data from the project to gain astonishing insights into the natural world.

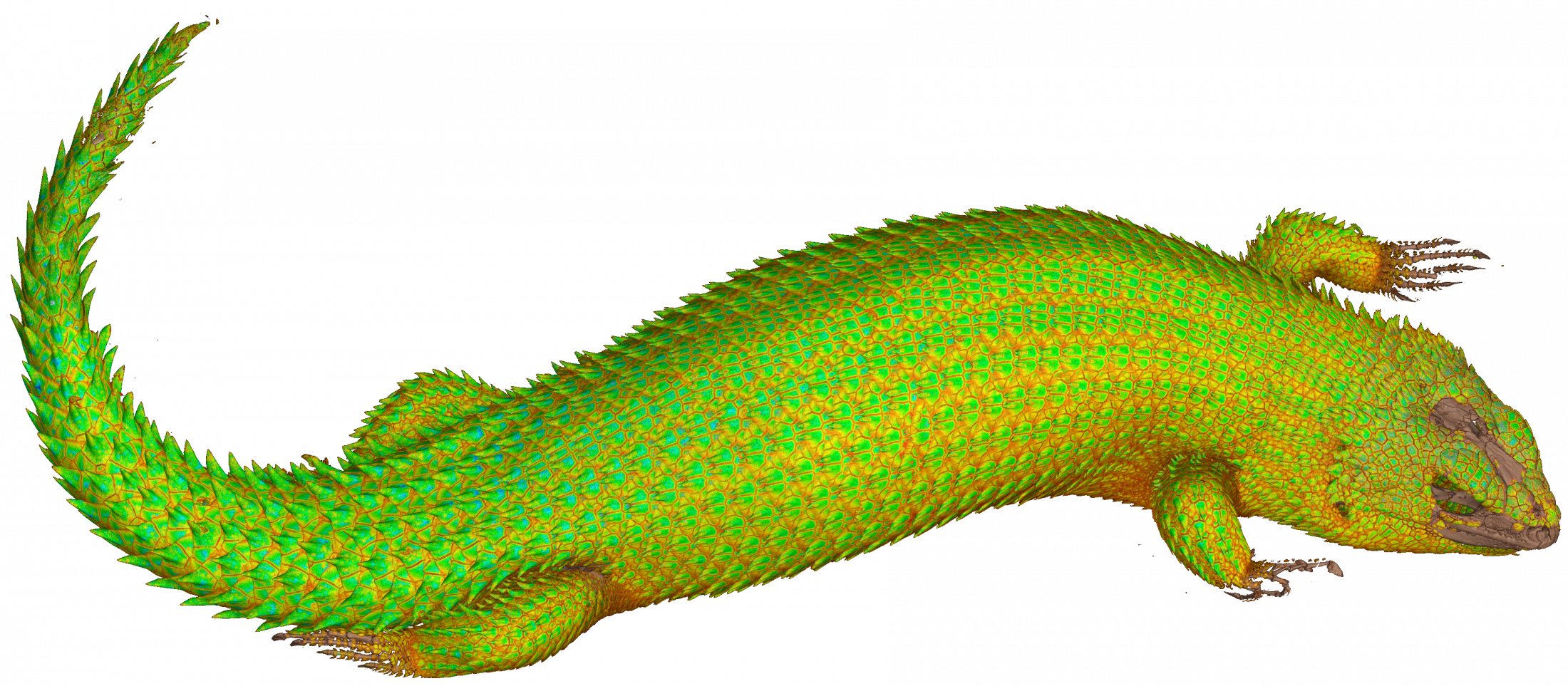

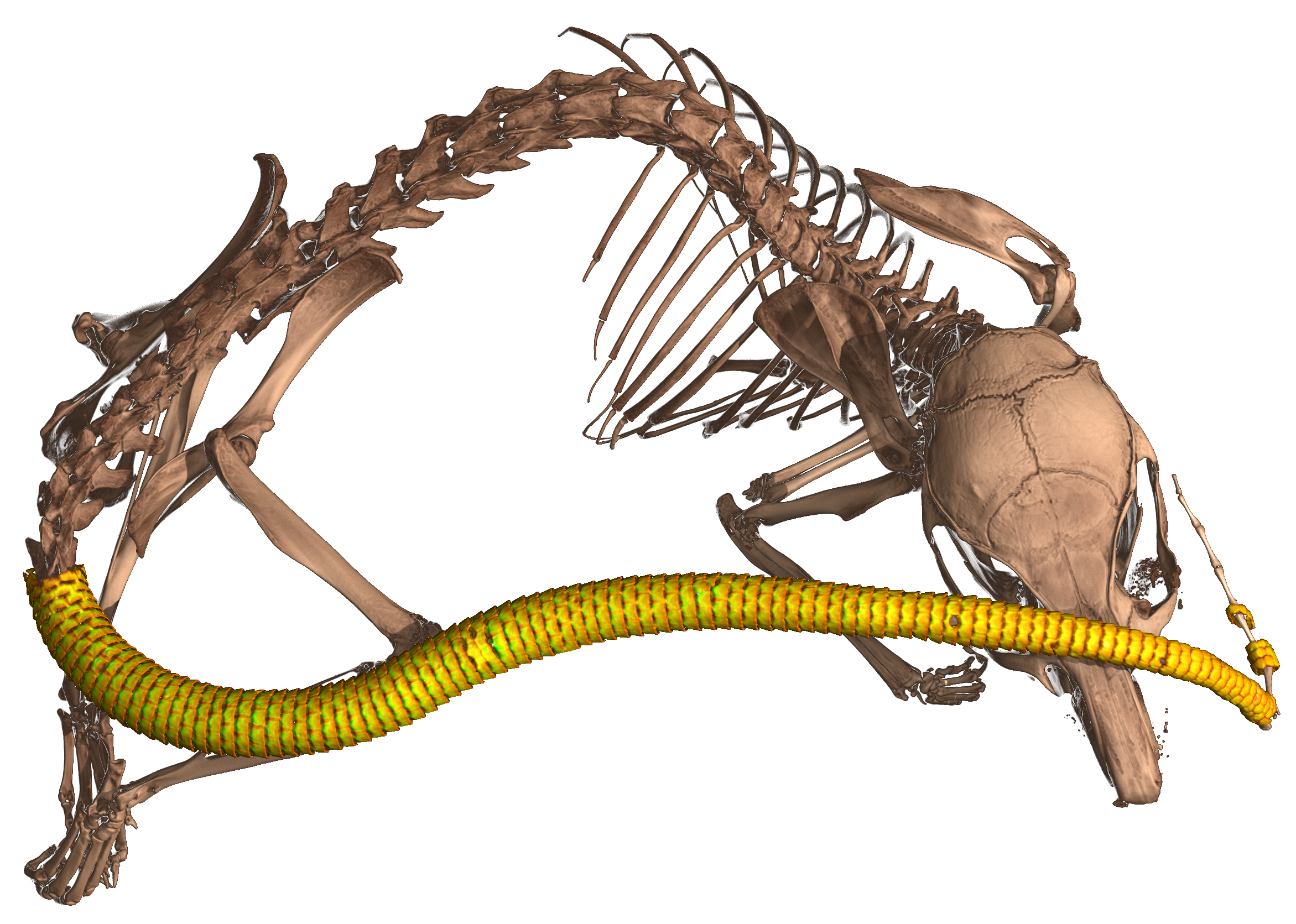

In 2023, Edward Stanley was conducting routine CT scans of spiny mice and was surprised to find their tails were covered with an internal coat of bony plates, called osteoderms. Before this discovery, armadillos were considered to be the only living mammals with these structures.

Image by Edward Stanley

“All kinds of things jump out at you when you’re when you’re scanning,” Stanley said. “I study osteoderms, and through kismet or fate, I happened to be the one scanning those particular specimens on that particular day and noticed something strange about their tails on the X-ray. That happens all the time. We’ve found all sorts of strange, unexpected things.”

CT scans from oVert were also used to determine what killed a rim rock crown snake, considered to be the rarest snake species in North America. Another study showed that a group of frogs called pumpkin toadlets had become so small that the fluid-filled canals in their ears that confer balance no longer functioned properly, causing them to crash-land when jumping. A massive study of more than 500 oVert specimens revealed that frogs have lost and regained teeth more than 20 times throughout their evolutionary history. And yet another study concluded that Spinosaurus, a massive dinosaur that was larger than Tyrannosaurus rex and thought to be aquatic, would have actually have been a poor swimmer, and thus likely stayed on land.

And the list goes on, full of insights and ideas that would have been impossible or impractical before the project’s outset. “Now that we’ve been working on this for so long, we have a broad scaffold that allows us to take a broader view of evolutionary questions,” Stanley said.

The value of oVert extends beyond scientific inquiry as well. Artists have used the 3D models to create realistic animal replicas, photographs of oVert specimens have been displayed as museum exhibits, and specimens have been incorporated into virtual reality headsets that give users the chance to interact with and manipulate them.

oVert models are also used by educators. From the outset of the project, Blackburn and his colleagues wanted to place a strong emphasis on K-12 outreach. They organized workshops where teachers could learn how to use the data in their classrooms.

“It’s been a game-changer for my evolution unit,” said Jennifer Broo, a high school teacher in Cincinnati. “I teach juniors and seniors, and I absolutely love them, but they can be a tough audience. They know when things are fake, which makes them less engaged. Using the oVert models, you can teach concepts at an appropriate level while also maintaining the authenticity of the science. My class has gotten so much better because I have had the opportunities to work with and expose my students to real data.”

There’s virtually no end to the number of things oVert could be used for. The biggest challenge will be creating tools that are sophisticated enough to analyze the data. Never before have this many 3D natural history specimens been publicly available and instantly accessible, and it will take further developments in machine learning and supercomputing to use them to their full potential.

“Generating the data is just the start,” said Jaimi Gray, a postdoctoral associate at the Florida Museum who’s working on NoCTURN (Non-Clinical Tomography Users Research Network), a project developed toward the end of oVert to make the best use of CT scans possible. “The aim of oVert was always to facilitate the exploration of vertebrate diversity. We’re going to keep exploring, but the goal of NoCTURN is to give people the tools to use the data, whether it’s for research, education or industry.”

Visit Sketchfab to view a sample of 3D interactive models.

Visit MorphoSource to access the full openVertebrate repository.

openVertebrate was funded by the National Science Foundation (grant no. DBI-1700908, no. 1701402, no. 1701516, no. 1701665, no. 1701713, no. 1701714, no. 1701737, no. 1701769, no. 1701797, no. 1701870, no. 1701932, no. 1701943, no. 1702143, no. 1702263, no. 1702421, no. 1702442, no. 1802491, no. 1902105, no. 1902242, no. 2001435, no. 2001443, no. 2001474, no. 2001652, no. 2101909, and no. RCN-2226185).

Additional authors on the study include Zachary Randall with the Florida Museum of Natural History, Doug Boyer and Julie Winchester with Duke University, John Bates, Daryl Coldren and Ben Marks with the Field Museum of Natural History, Stephanie Baumgart with the University of Florida, Emily Braker with the University of Colorado, Kevin Conway and Heather Prestridge with Texas A&M University, Alison Davis Rabosky, Ramon Nagesan, Gregory Pandelis and Daniel Rabosky with the University of Michigan, Noé de la Sancha with DePaul University, Casey Dillman with Cornell University, Jonathan Dunnum with the Museum of Southwestern Biology, Catherine Early with the Science Museum of Minnesota, Benjamin Frable the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, Matt Gage and James Hanken with Harvard University, Jessica Maisano with the University of Texas at Austin, Katherine Maslenikov, Adam Summers and Luke Tornabene with the University of Washington, John McCormack with Occidental College, Mark Robbins and Luke Welton with the University of Kansas, Lauren Scheinberg with the California Academy of Sciences, Carol Spencer with the University of California, Berkeley, Leif Tapanila with Idaho State University and Greg Watkins-Colwell with Yale University.

Sources: David Blackburn, dblackburn@flmnh.ufl.edu;

Edward Stanley, elstanley@flmnh.ufl.edu

Jaimi Gray, jaimigray@floridamuseum.ufl.edu

Media contact: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452