In the summer of 2020, Florida Museum researchers Tobias Grun and Michał Kowalewski dove into the shallow waters off the coast of the Florida Keys and scoured the ocean floor for sea urchins. Telltale tracks and dimples in the sediment alerted them to the presence of sand dollars, sea biscuits and heart urchins concealed just beneath the surface.

Between August and April of the following year, Grun and Kowalewski visited 27 sites along a 20-mile stretch of coast near Long Key. By the time they finished, their sea urchin survey was among the most extensive conducted in the region for the last several decades, and their results offer a bit of good news.

The researchers published an analysis of their survey last week in the journal PeerJ, which shows the number and diversity of sand dollars, sea biscuits and heart urchins appears to have remained relatively stable since researchers began keeping tabs on their populations in the 1960s.

“It was a pleasant surprise to find that they’re still widespread and abundant,” said study co-author Kowalewski, the Florida Museum Thompson Chair of Invertebrate Paleontology. “The Florida Keys are heavily impacted by human activity, with fishing, tourism and diving all occurring on a massive scale. On top of that, coastal ecosystems are subject to climate change, increasingly strong hurricanes and escalating stressors resulting from continuous urban development.”

Sea urchins are essential for healthy marine ecosystems

Sea urchins are echinoderms, the name derived from a mix of Greek and Latin meaning “spiny skin.” They’re closely related to starfish, brittle stars, sea lilies and sea cucumbers, and they include two types: regular and irregular.

Sea urchins of the first type are spherical in shape and covered in a formidable network of spines, giving them the appearance of medieval morning stars. Each spine can be pointed in the direction of a threat and provides a measure of protection as they graze on algae in open seagrass meadows, mangrove shoals and coral reefs.

Images from Grun and Kowalewski, 2022

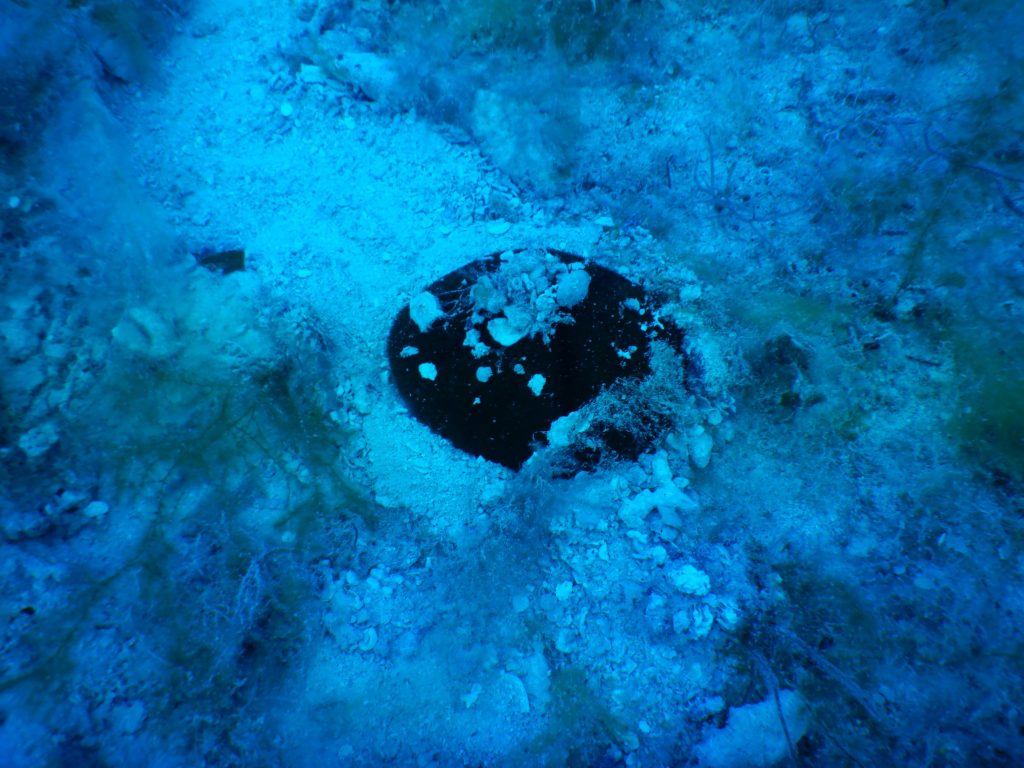

Irregular echinoids, which include sand dollars, sea biscuits and heart urchins, are the unsung Roombas of the seafloor. Unlike their prickly surface-dwelling relatives, most sand dollars and sea biscuits are burrowers, with short, locomotive spines they use to crawl and deposit food in grooves along their skin, which run like conveyer belts directly to their mouths. Others, such as the cake urchin (Meoma ventricosa), simply scoop up anything in their path.

As they tunnel their way through sand, silt and mud in an endless quest for food, they clean, ventilate and enrich the sediment, making it more hospitable to other organisms.

By changing the landscape, they function as ecosystem engineers, explained lead author Grun, a postdoctoral researcher at the Florida Museum. “They’re essential for maintaining healthy environments. They feed on detritus and help oxygenate the sediment, which allows microorganisms to degrade waste,” he said.

There are also a lot of them. In certain areas, irregular urchins can be among the most abundant animals by volume on the seafloor. This is especially true in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea, where dozens of species inhabit sprawling shelf platforms.

Sand dollars and heart urchins stand the test of time in deteriorating environments

Despite their importance and abundance, sea urchins are often given short shrift when it comes to marine surveys. In the denuded Florida Keys, considerable effort has been extended to document the decline of coral, fish, seagrass and manatees, but only a handful of widescale sea urchin surveys have been carried out over the last 60 years.

According to a 2020 report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Florida’s coral reefs have become impaired in recent decades due to a combination of factors. Increased global temperatures have resulted in six mass coral bleaching events in South Florida since 1987, and in 2014, an outbreak of stony coral tissue loss disease was reported on reefs near Miami. The disease has spread every year since and now affects the entirety of Florida’s barrier reef, from Martin County in central Florida to the furthest tip of the Florida Keys.

Delicate seagrass meadows are additionally reeling from the combined effects of climate change, pollution and the reduced influx of freshwater from the Everglades; Florida’s mangrove forests are at risk from increasingly intense tropical weather events; and a 2022 study determined that, of 15 grouper and snapper species popular among recreational fisheries, 85% were being harvested past the point of sustainability in the Florida Keys.

Given the paucity of available data on sea urchins, it was unclear how their populations may have fared amid the degradation of the surrounding ecosystems.

“One of the reasons we conduct these surveys is to get a better numerical understanding of how important and abundant these organisms are because right now, that documentation is spotty,” Kowalewski said.

Grun and Kowalewski caution that this survey offers only a small snapshot of sea urchin diversity in the Florida Keys. But if their results are at all indicative of nearby benthic habitats, then sand dollars, sea biscuits and heart urchins seem to have mostly evaded the negative consequences of environmental change.

Irregular urchins were present at the majority (63%) of surveyed sites, from sheltered seagrass meadows along the coastline to deeper mudflats on the far side of the barrier reef. When they found living urchins, they often noted the waferlike discs of dead individuals disintegrating in the sediment, a sign that populations may have persisted in place for multiple generations.

According to Grun, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly why sea urchins have remained unaffected, but he suspects the relative disregard people have for them might play a role. “These sea urchins are neither of commercial nor of recreational interest, and their sandy habitats are not often visited by fishers or divers,” he said.

Whether sea urchins in the Florida Keys will carry on unscathed as temperatures continue to rise and oceans become increasingly acidic remains an open question.

“We’re planning on looking more into the environmental factors that affect sea urchins, such as sediment and water composition, over the next years,” he said, stressing that the amount known about sea urchins is dwarfed by what’s left to be discovered. “We’re entering a new arena of research in which we’d really like to drive home the importance of these organisms and highlight their role as ecosystem engineers.”

Funding for the study was partially provided by the German Research Foundation (GR5464/1) and the National Science Foundation (EAR-1630276 and EAR-2127623).

Sources: Tobias Grun, tgrun@ufl.edu;

Michał Kowalewski, mkowalewski@flmnh.ufl.edu

Writer: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452