Shark attacks decreased for the third consecutive year, falling to 57 unprovoked bites worldwide in 2020, compared with 64 bites in 2019 and 66 in 2018, according to the annual summary issued by the University of Florida’s International Shark Attack File. The most recent five-year global average sank to 80 incidents annually.

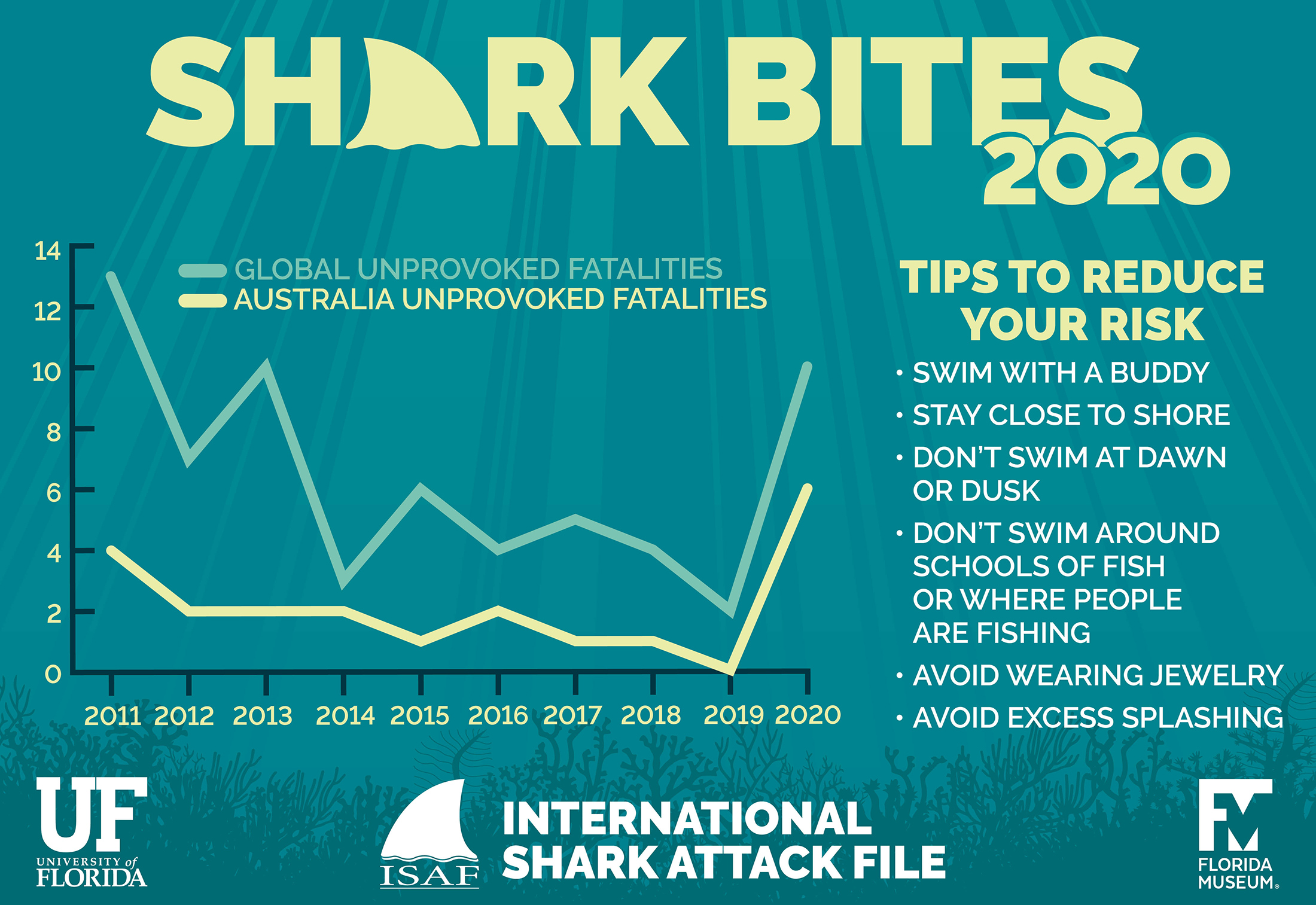

But it was the deadliest year since 2013, with 10 unprovoked bites resulting in fatalities, a stark departure from the average of four per year. Six of the fatal bites occurred in Australia, three in the U.S. and one in the waters of St. Martin in the Caribbean.

Consistent with long-term trends, the U.S. led the world in number of bites, with 33 incidents, a 19.5% drop from 41 last year. Australia followed with 18, a slight uptick from the country’s most recent five-year average of 16 bites per year.

Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s shark research program, said the high number of deaths in 2020 is likely an anomaly.

“It’s a dramatic spike, but it’s not yet cause for alarm,” he said. “We expect some year-to-year variability in bite numbers and fatalities. One year does not make a trend. 2020’s total bite count is extremely low, and long-term data show the number of fatal bites is decreasing over time.”

Image by Jane Dominguez/University of Florida

Experts also confirmed single, non-fatal bites in the Republic of Fiji, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, New Zealand and Thailand.

ISAF investigates all human-shark interactions, but focuses its report on unprovoked attacks, which are initiated by a shark in its natural habitat with no human provocation. These exclude bites to boats, scavenging and bites in public aquariums.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on shark bite numbers

The past three years have marked an abrupt drop in global shark attacks from previous totals in the high 80s. 2017’s 88 unprovoked bites, for example, were average at the time. Still, 2020’s total of 57 bites worldwide represents a larger-than-expected decrease from 2019 and 2018, Naylor said.

It remains unclear whether COVID-19 lockdowns and a slow year for tourism might have contributed to an unusually low number of bites – or if the dip reflects the difficulty in getting data during a pandemic.

While a certain number of cases remain unconfirmed and unclassified each year, this situation was exacerbated in 2020, said Tyler Bowling, ISAF manager. With law enforcement, coroners and healthcare workers focused on responding to COVID-19, few had time to help confirm reported shark bites or provide extra information about incidents.

As a result, Bowling is still working to confirm 16 reported bites and classify an additional six confirmed bites as unprovoked or provoked. In contrast, nine incidents were unconfirmed in 2019 and nine were confirmed as shark bites, but could not be classified. All open cases remain under investigation, Bowling said.

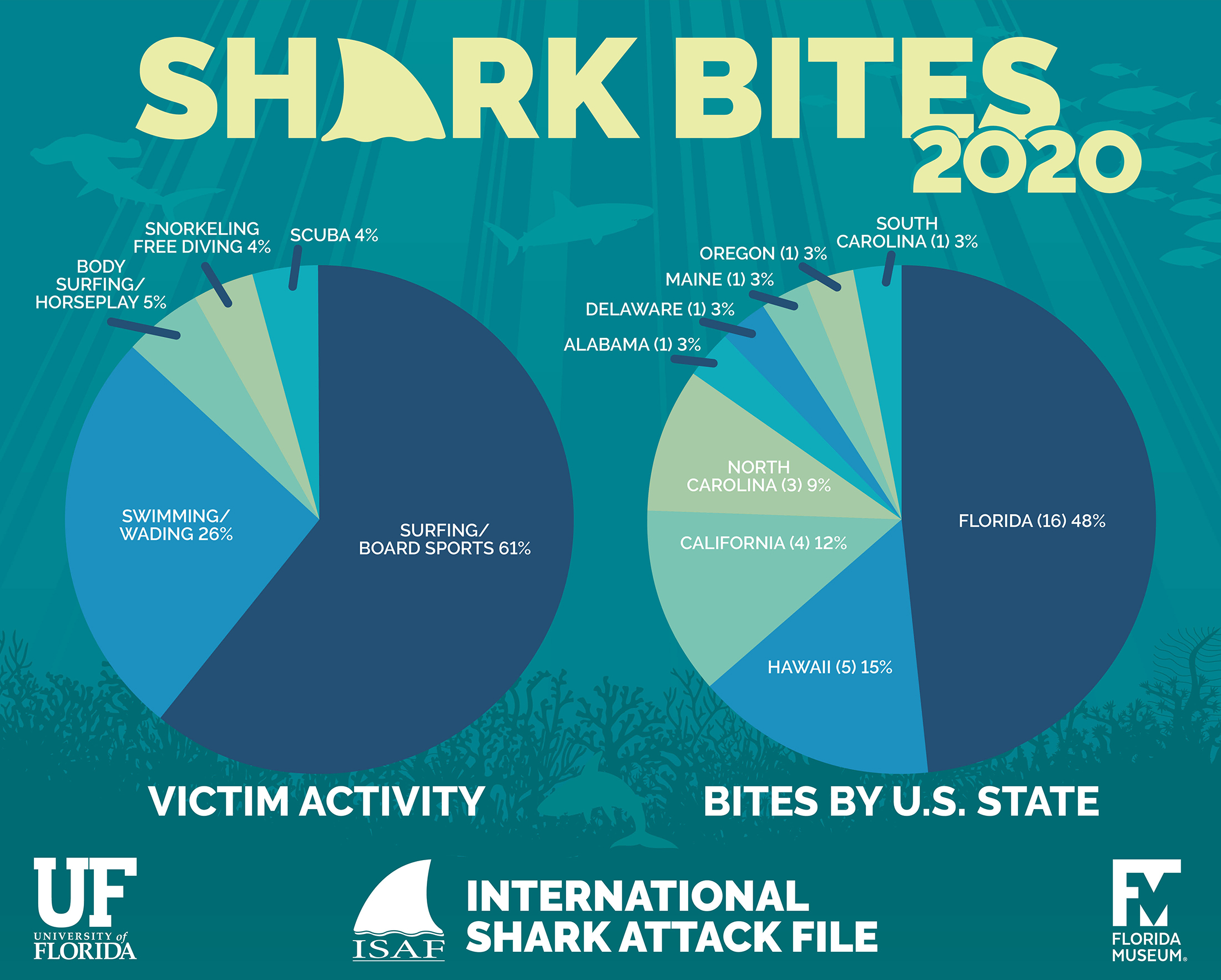

Surfers and other board sport athletes, largely undeterred by the pandemic, experienced 61% of bites worldwide in 2020, compared with 53% in 2019 and 2018.

Image by Jane Dominguez/University of Florida

Florida continues to dominate U.S. bite total

With 1,350 miles of coastline and a large surfing community, Florida has long been a global hotspot for shark bites, a trend that continued in 2020. The state’s 16 unprovoked bites accounted for about 48% of the U.S. total and 28% of incidents worldwide, though the total was significantly lower than Florida’s five-year annual average of 30.

Eight of the bites happened in Volusia County, followed by three in Brevard and single attacks in Duval, Martin, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach and St. Johns counties.

Other states with unprovoked bites include Hawaii, 5, California, 4, and North Carolina, 3, with single incidents in Alabama, Delaware, Maine, Oregon and South Carolina. Three of the bites proved fatal, one each in California, Hawaii and Maine, a first for the state.

Major year for white shark bites

ISAF experts confirmed great white sharks were involved in at least 16 unprovoked bites in 2020, including six of the year’s 10 fatalities: four in Australia, one in California and one in Maine. Of the remaining deaths, two were from tiger shark bites and two could not be identified to species.

While some scientists have suggested various reasons for the high number of bites caused by white sharks in 2020 – global warming, changing fish populations and migrations or even “rogue” sharks – Naylor cautioned against jumping to conclusions.

“We need to focus on long-term trends and rigorous scientific study, rather than speculation,” he said. “I think the frequency of white sharks swimming in the same places as humans may be on the rise, but if so, we don’t yet know the cause.”

He noted that while Australia was hard-hit with fatalities in 2020, the total number of bites in the region was not exceptional: “It’s just that the fraction of bites that resulted in fatalities was higher.”

Image by Jane Dominguez/University of Florida

Encounters with white sharks can result in more serious wounds, due to the species’ size and power, Naylor added.

“A blacktip can give you four stitches while a nibble from a white shark can remove your leg,” he said. “They’re supremely better swimmers than humans, and they’ve got a nasty set of choppers at the front.”

But Naylor and Bowling said there is no evidence sharks are actively hunting humans and that most bites occur when sharks mistake people for fish, seals or other animals. They cited examples of drone footage showing sharks, including white sharks, approaching and circling surfers and swimmers before jetting in the opposite direction.

“They’re normally more curious than anything else,” Bowling said.

While the chances of being bitten by a shark are minimal, ISAF offers recommendations for how to lower the risk of a shark attack or fend off an attacking shark.

Sources: Gavin Naylor, gnaylor@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1954;

Tyler Bowling, tbowling2@ufl.edu, 352-273-1949