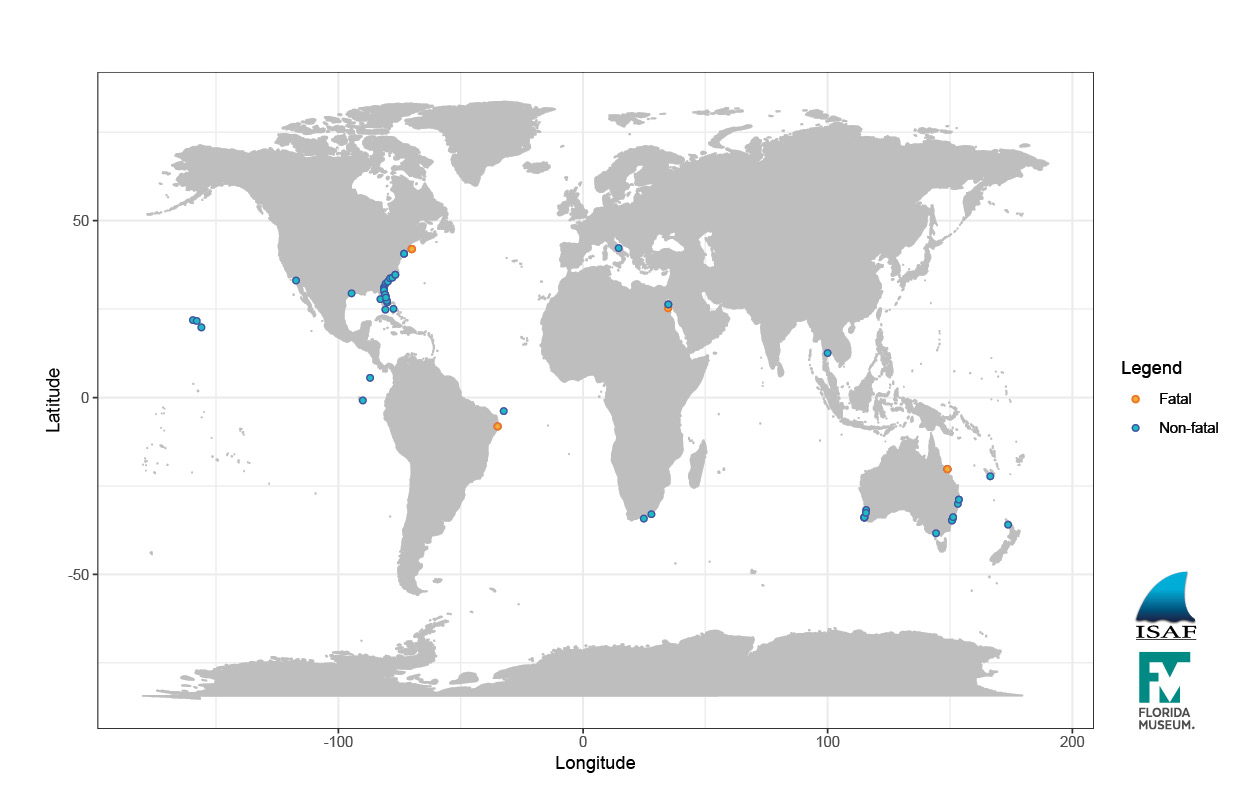

While several high-profile shark bites made headlines last year, the total number of shark attacks globally took a nosedive. The University of Florida’s International Shark Attack File reported 66 unprovoked shark bites in 2018, down from 88 in 2017 and 26 percent lower than the most recent five-year average of 84 incidents annually.

Four of the bites proved fatal, roughly keeping in line with the average of six deaths worldwide per year. Consistent with long-term trends, the U.S. led the world in attacks with 32 bites, a drop from 53 the previous year.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

Year-to-year fluctuations in the number of shark bites are normal, but 2018’s steep decline is unusual, said Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s shark research program.

“Statistically, this is an anomaly,” he said. “It begs the question of whether we’re seeing fewer bites because there are fewer sharks – that would be the ‘glass half-empty’ interpretation. Or it could be that the general public is heeding the advice of beach safety officials. My hope is that the lower numbers are a consequence of people becoming more aware and accepting of the fact that they’re sharing the ocean with these animals.”

Naylor said press coverage of two great white shark bites in Cape Cod, Massachusetts – one of which was fatal – and the uncommon phenomenon of two bites occurring within minutes of one another off Fire Island, New York, gave the illusion that 2018 was a “a big year for shark bites.”

But in reality, total unprovoked bites decreased in the U.S. and abroad, with a few exceptions. The ISAF defines unprovoked shark attacks are those initiated by a shark in its natural habitat.

Florida Museum image by John Denton

Australia saw an uptick in bites with 20, including one fatality, an increase from the region’s recent five-year average of 14 bites annually. Brazil and Egypt both had three bites and one fatality, up from a single non-fatal bite each in 2017.

The ISAF confirmed two bites in South Africa and continues to investigate four unclassified attacks in the region. Single bites occurred in the Bahama Islands and Costa Rica – a drop from two each the year before – and the Galapagos Islands, New Caledonia, New Zealand and Thailand.

A rash of bites over the past few years at Reunion and Ascension islands signaled they could be emerging attack hotspots, but the islands reported no bites in 2018. Naylor credited Reunion Island’s stringent attack mitigation strategies as contributing to fewer bites.

Similarly, no attacks were recorded in the Canary Islands, Cuba, England, Japan and the Maldives, each of which had a single incident in 2017.

Florida, which annually tops the leaderboard for attacks in the U.S., reported 16 unprovoked bites, down from 31 in 2017, and Volusia County, the shark attack capital of the world, had four bites, compared to nine the year before.

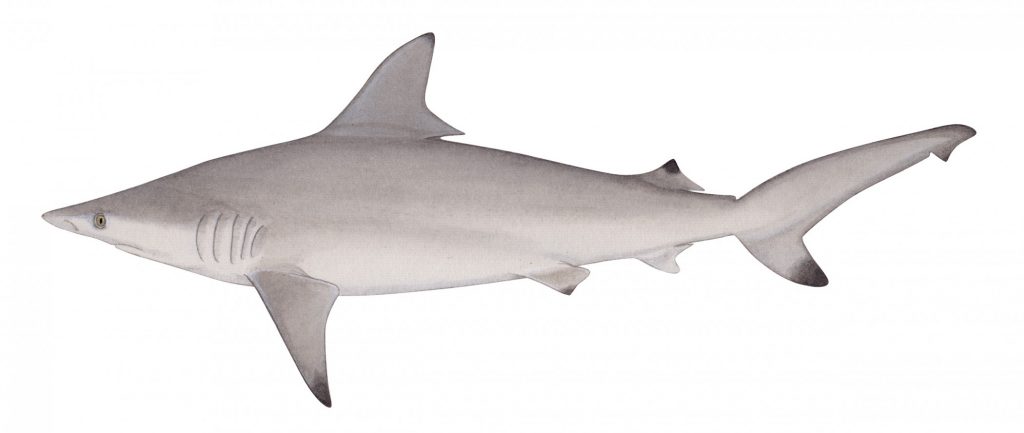

Naylor cited the apparent shrinking of the state’s blacktip shark populations – the species most commonly involved in Florida shark bites – as a possible factor in the downturn in attacks.

“Blacktips used to amass in huge numbers along the coast of Florida, and there have been far fewer of them, particularly in the last two or three years,” he said. “The fact that numbers of that particular species appear to be diminishing would be consistent with the number of bites being a little lower than in past years.”

Illustration by Lindsay Gutteridge

Hawaii, North Carolina and South Carolina had three bites each; two bites occurred in Massachusetts and New York; and California, Georgia and Texas reported single bites.

Shark bites globally are on a slow, gradual rise, a direct result of the increasing number of people in the water. But fatality rates worldwide have been on the decline for decades, which Naylor attributes to the swift and effective responses of beach safety officials.

Naylor said one area to watch is Cape Cod, which experienced two great white attacks, including the community’s first fatality in 82 years. Great whites are returning to the area as local seal populations rebound, a result of the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

“An increase in sharks is a symptom of restoring healthy oceans,” Naylor said. “What the public needs to do is become informed about these animals, understand their behavior patterns and listen to the guidelines issued by beach safety patrols.”

Illustration by Lindsay Gutteridge

Fifty-three percent of bites involved board sports, which are typically practiced in the surf zone where sharks commonly swim and can produce the kind of water disturbance that could attract a shark.

While the chances of being bitten by a shark are minimal, the ISAF offers recommendations for how to lower the risk of a shark attack or fend off an attacking shark.

Naylor said a goal of the museum’s shark research program is to increase the use of DNA as a means of identifying shark species responsible for bites, a technique his lab successfully tested with a tooth fragment recovered from one of the Fire Island attacks. The program also aims to help the public appreciate the diversity and biology of the more than 500 known species of sharks.

“Only about 5 percent of shark species have been implicated in bites,” Naylor said. “As we fine-tune our understanding of these animals, we not only increase our own safety in the water, but we can turn fear to fascination.”

Read ISAF’s summary of 2018’s shark attacks.

Source: Gavin Naylor, gnaylor@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1954

Learn more about the Florida Program for Shark Research at the Florida Museum.