This Halloween season, we’re celebrating a part of Florida’s natural history that’s often underappreciated: fungi, parasites and wasps. We’ve also thrown in a few plants for good measure. Each of these groups is an integral part of Florida’s biodiverse ecosystems, and each provides a uniquely lurid look at nature’s endless transformations into beautiful — and sometimes terrifying — forms.

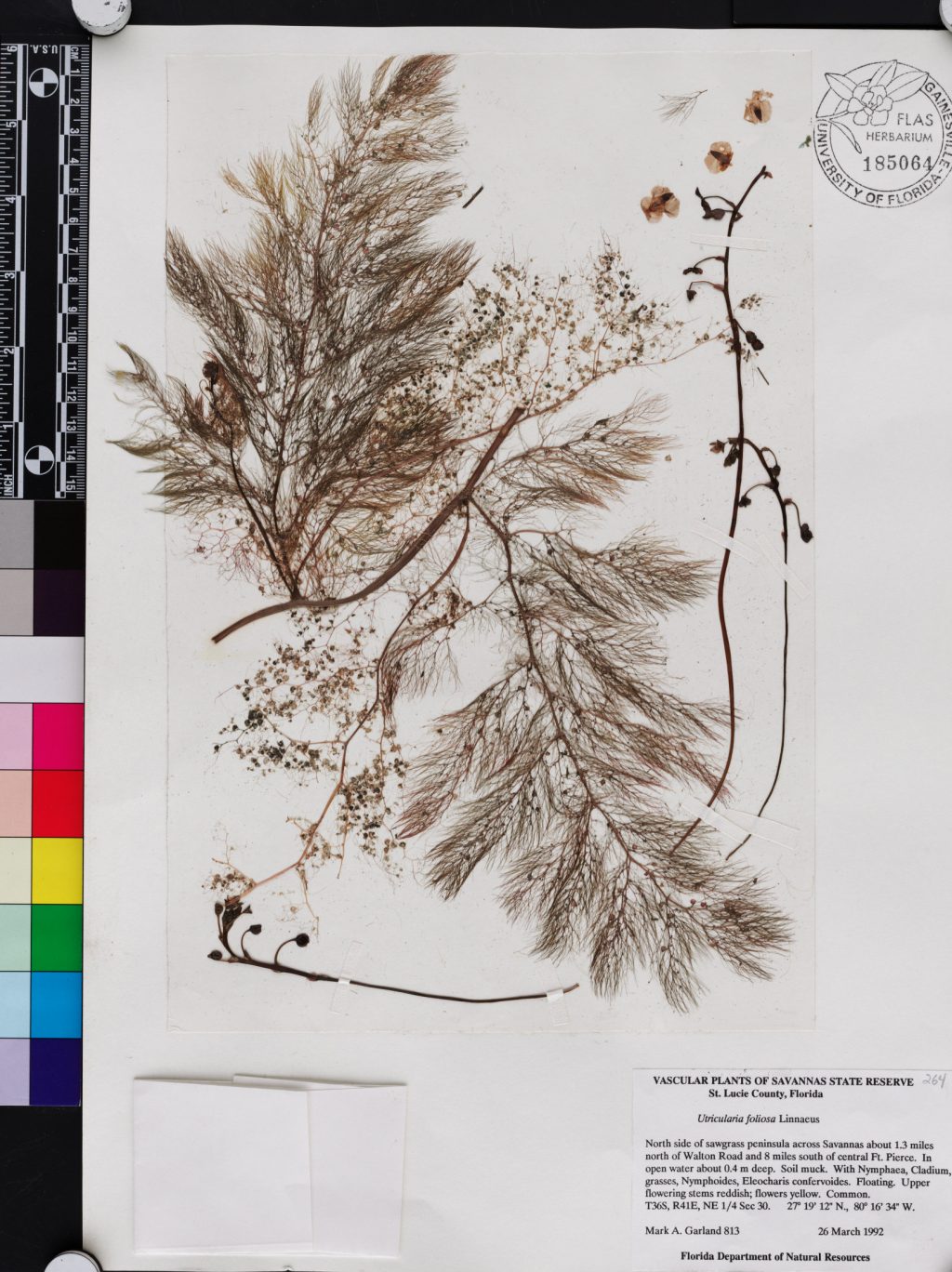

Devil’s tooth fungus (Hydnellum peckii)

Photo by ngkoons, CC BY-NC

Straight out of John Carpenter’s “The Thing,” this alien fungus is sure to unsettle even the bravest mycologists. When it absorbs excess moisture, it exudes a red liquid that looks like blood from pores in its cap. The crimson color is the result of water mixing with red terphenylquinone pigment in the mushroom.

The underside of the mushroom is equally unsettling. Many mushrooms produce spores in furrows or pores on the underside of their caps, but — as its name suggests — the devil’s tooth fungus uses teeth instead. These fungal fangs aren’t real teeth. Instead, they’re made of mycelium like the rest of the mushroom, and their elongated, toothlike shape provides more surface area to produce spores.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

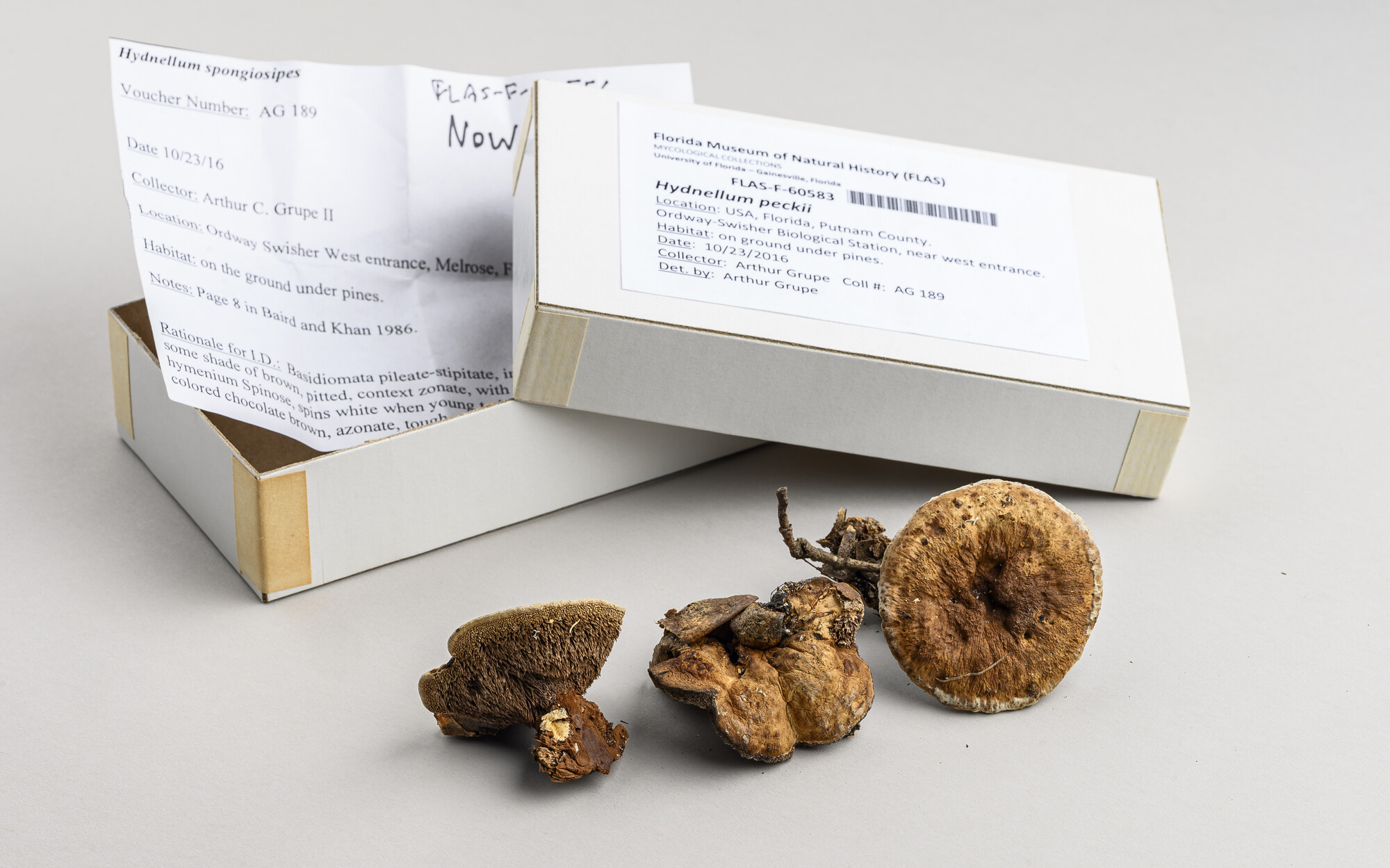

Dead man’s fingers (Xylaria polymorpha)

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Like an omen, dead man’s fingers grow at the base of dead and dying plants. Often bent and swollen, as if afflicted with arthritis, the fungal growths bear an uncanny resemblance to their namesake. When younger fungal bodies appear in the spring, they even produce a layer of pale, sometimes blue, asexual spores on their surface that often resemble fingernails.

This wood-rotting fungus grows on trees and shrubs, where it breaks down glucan, a chain of carbohydrates that binds the cell walls in wood together. After the fungus has made its meal of the rotting wood, all that’s left of the stump is a soft mass of cellulose and lignin that insects or other fungi can consume.

Dead man’s fingers grow throughout eastern North America, including Florida. It often appears on American elm, pear and plum trees and darkens until it is mature in summer or fall. Each of its “fingers” has a tiny hole for releasing sexual spores. Removing the above-ground portion of the fungus can reduce the spread of the spores but does nothing to slow the decomposition happening in the soil.

Photo by Jerald Pinson, CC0

Winter worm summer grass (Ophiocordyceps sobolifera)

An ancient Chinese text from the Tang Dynasty (AD 618- AD 907) and Tibetan manuscripts written in the 15-16th centuries reference a shape-shifting organism that lives out the winter as a worm and transforms into a plant during the summer.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

This fanciful creature may seem like the stuff of myth, but it’s actually a fairly good description of a fungus that infects certain insects, including moths and cicadas.

If you live someplace warm, you’re probably most familiar with large adult cicadas, which ascend to the forest canopy in droves and emit a shrill, deafening chorus. But this is just the tail end of their lifecycle. Cicadas spend most of their lives as larva (worm-like, juvenile insects) and more developed nymphs, which live underground and chew on roots.

In many areas, including Florida, these juvenile cicadas are susceptible to a fungal infection that eats away at their insides and engulfs the cicada in a hardened sphere of wispy filaments called hyphae. At the onset of warmer weather, the fungus produces fruiting bodies that grow out of the cicada’s head and emerge above ground, where its spores are distributed by wind.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

The Chinese and Tibetan text likely refer to a closely related fungal species, Ophiocordyceps sinensis, which similarly parasitizes ghost moths in the family Hepialidae.

Cicada killer wasps (Sphecius speciosus)

By Halloween, many cicadas will have undergone unimaginable horror at the hands of the cicada killer wasp.

Photo by Alejandro Santillana, Insects Unlocked, CC0

Measuring up to 2 inches long, cicada killer wasps are among the largest insects in the order Hymenoptera, a group that also includes ants and flies. They evolved their disturbingly large proportions to abduct cicadas, which are themselves large insects.

Throughout July and September, female cicada killer wasps mate, dig nesting burrows in soil and hunt for cicadas. The wasp paralyzes its prey with a venomous sting, then climbs a tall object, like a tree, so she can glide back to the nest with her immobilized captive in tow.

Photo by kszafrajda, CC BY

Back in the burrow, the wasp lays an egg on top of the unlucky cicada and seals up the entrance on her way out. She repeats the process to fill around 15 egg chambers.

Later, the egg hatches into a larva that eats the cicada alive, gaining fuel to grow and spin a cocoon. It remains below ground through the winter as it transitions into a pupa before emerging in the summer as an adult, ready to start the cycle all over again.

Despite their intimidating name and appearance, cicada killer wasps are rarely aggressive toward humans and play an important role in keeping ecosystems balanced by controlling cicada populations. Male wasps may fly toward people that get too close to a nesting location, but they lack stingers and are completely harmless. The females do not have a nest-protecting instinct and will only sting if directly provoked.

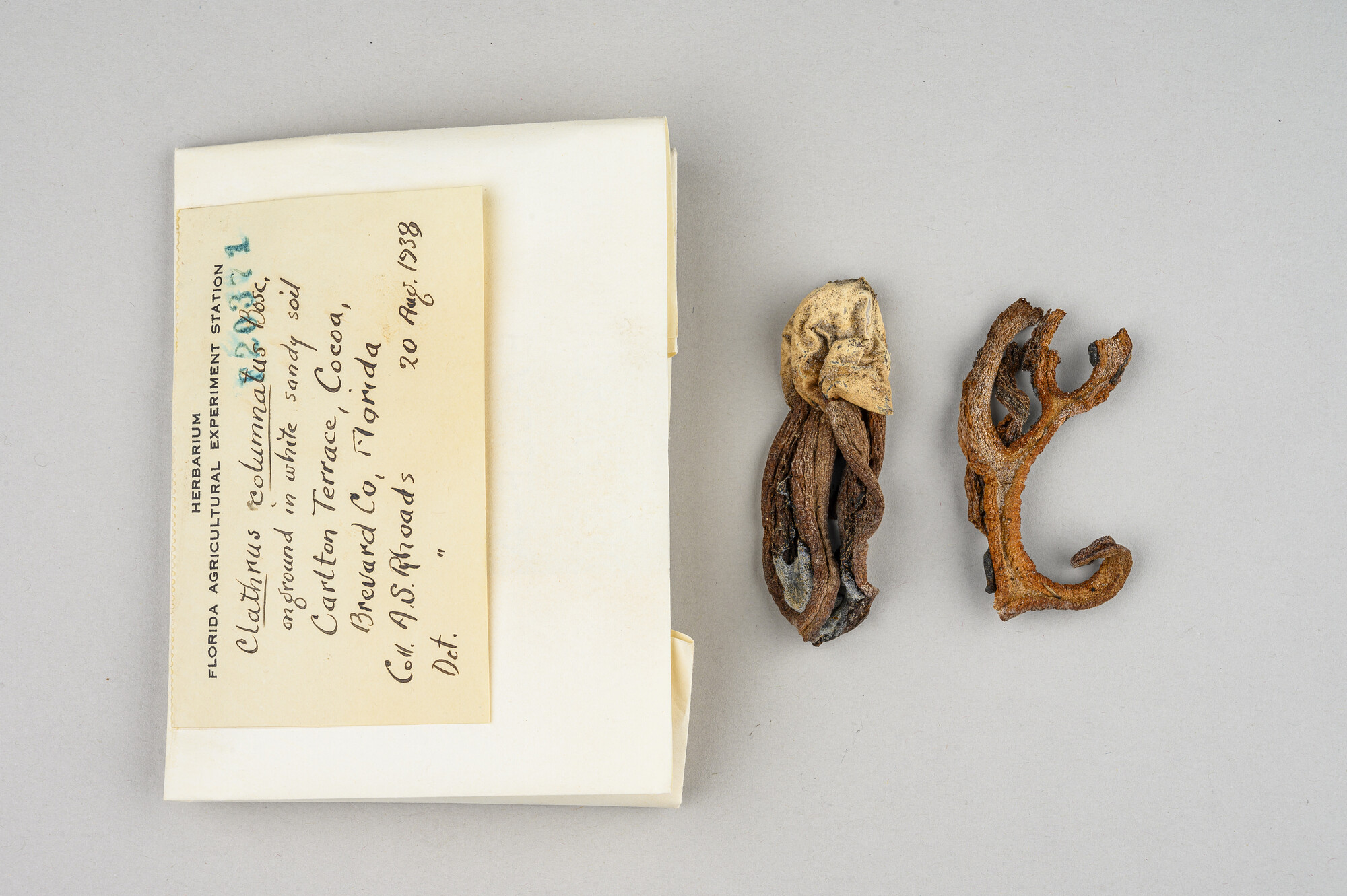

Columned stinkhorn (Clathrus columnatus)

A strange, alienlike egg has appeared in your home garden. It is the columned stinkhorn, a fungus that grows on decaying plant material and receives nutrients from bacterial activity in rotting wood.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Inside the white, round structure, a brown gelatinous substance encases the immature fruiting body until it is ready to emerge. Once it does, two to five spongy, orange-red columns will appear, curled like tentacles and sometimes merging at the top in a squishy arch.

Photo by Alex Abair, CC BY-NC

The smell will hit you before you lay eyes on it. Stinkhorns are aptly named, with an odor similar to rotting flesh or feces — or both. Unlike many other mushroom-forming fungi, the columned stinkhorn does not disperse its spores by releasing them into the wind but by recruiting other organisms.

At the top of its stalks, the stinkhorn produces a slimy mass of spores known as the gleba. While the smell may be repugnant to humans, it’s irresistibly alluring to some insects and other invertebrates. As they crawl and fly around the columned stinkhorn, insects pick up a small amount of the brown, spore-embedded slime, which they later deposit on the next surface they rub against next.

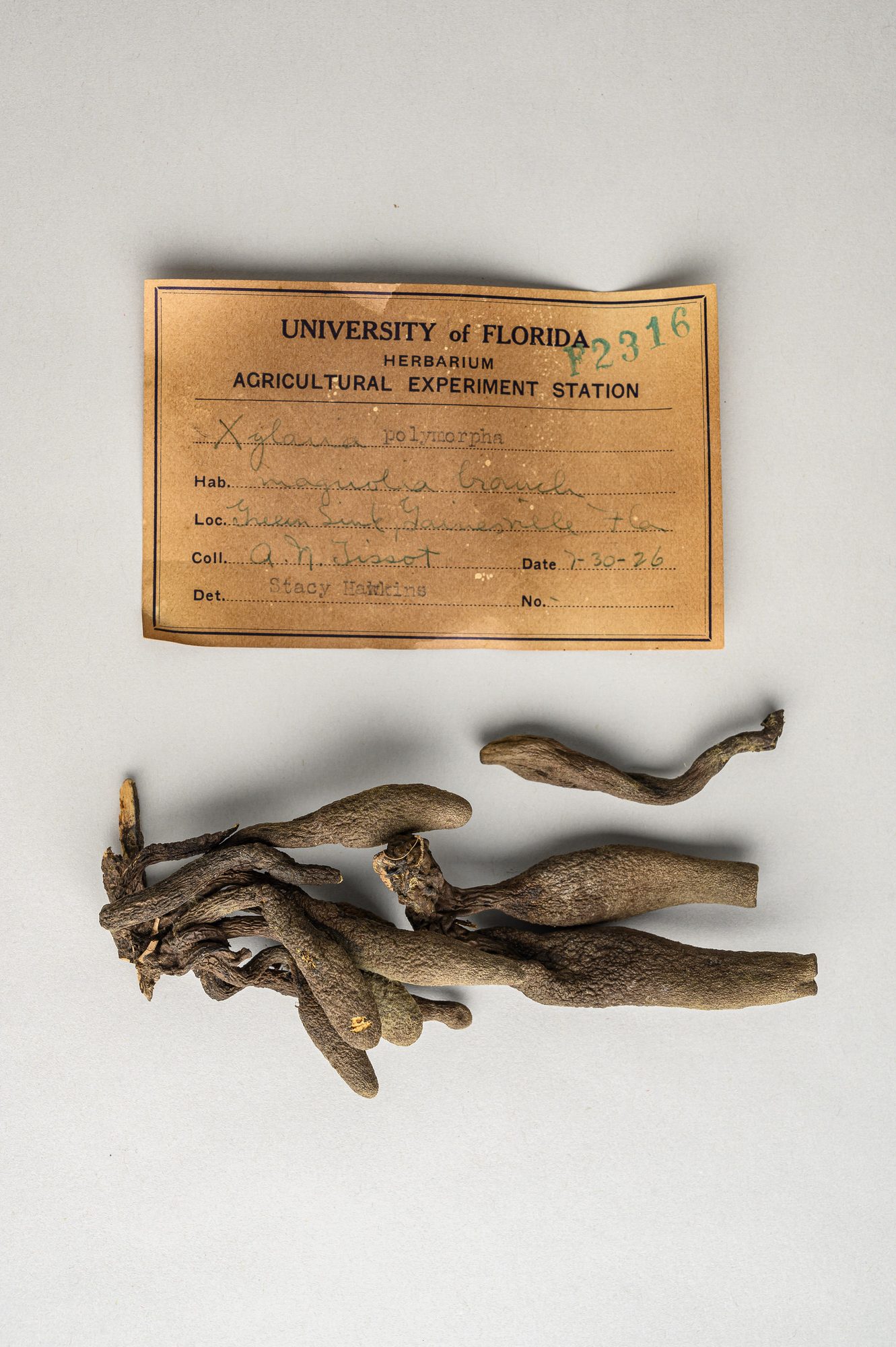

Bladderwort (Utricularia spp.)

Bladderworts can be found lurking in freshwater all over the world, and they’re especially diverse in Florida, which boasts 14 native species. Bladderworts may look like regular aquatic plants, but don’t be fooled. Beneath the water’s surface, each plant produces hundreds of water-filled sacs called utricles or bladder traps.

Photo by Gilles Ayotte, CC BY-SA

The trap is one of the fastest, most sophisticated and deadliest structures in the plant kingdom, and bladderworts use them to abduct and digest prey.

For the trap to work, specialized glands push some, but not all, of the water out, creating a bubble of air and a pressure differential inside. When the unsuspecting insect, protozoan or fish fry wanders too close, its movement triggers the tiny hairs on the outside of the trap.

In less than one-hundredth of a second, the trap door mechanically buckles and caves in, acting as a vacuum and dragging the victim inside. The door quickly closes, and the trap secretes enzymes to break down its prey. A cabal of hungry bacteria and fungi that live inside the utricles help speed up digestion. The speed of this capture mechanism is so remarkably fast that scientists couldn’t figure out how it worked until the invention of high-speed cameras.

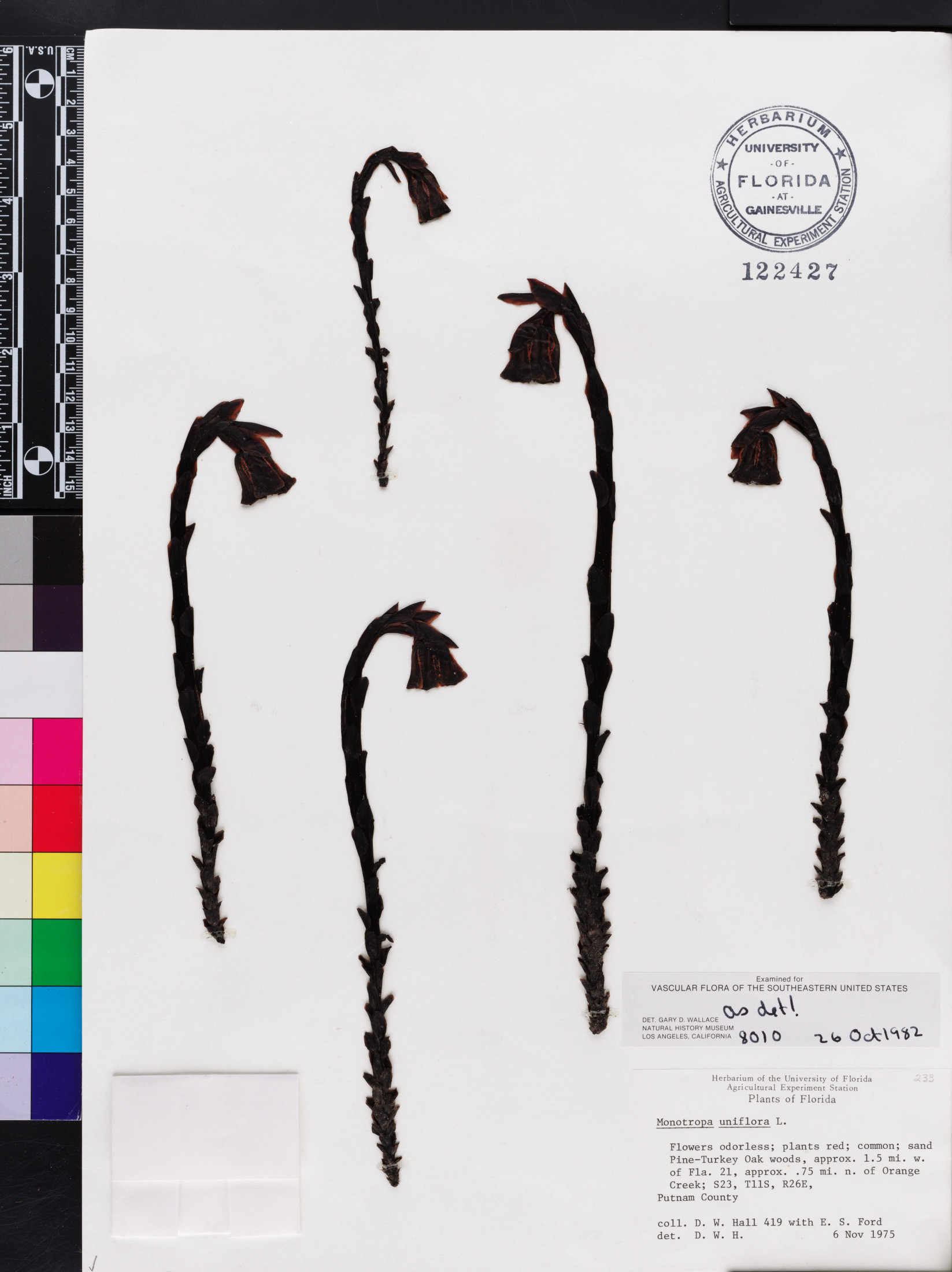

Scrub ghost pipe (Monotropa brittonii)

You may see ghost pipes out of the corner of your eye, growing beneath the trees in the deep, shady wilderness. These plants spend most of their lives hidden away underground, but when conditions are right, they emerge from the shadows with frightening flowers.

Photo by Liz West, CC BY

Their ghastly stalks and flowers are eerily white and turn a dark coal black when they die. Ghost pipes have no chlorophyll, and they don’t photosynthesize. Instead, they indirectly steal nutrients from other plants by tapping into a massive subterranean network of fungi.

Mycorrhizae are fungi that creep and crawl through the soil and connect to roots, acting as a bridge between plant worlds. At least 80% of plants are known to have symbiotic relationships with underground fungi. Plants give sugars from photosynthesis to their fungal friends in exchange for water and nutrients from the soil. Mycorrhizae also create a sort of below-ground information highway, allowing plants to pass along signals to each other.

Ghost pipes hack into this fungal wood wide web and feed off the nutrient exchange network. It’s a hauntingly unique method of obtaining nutrients. Ghost pipes are also referred to as fungus flowers, since they look like pale mushrooms peeking up from the soil. Their flowers attract bumblebees and are oriented toward the ground to keep out rain. They closely resemble the flowers of blueberries and cranberries, to which ghost pipes are closely related.