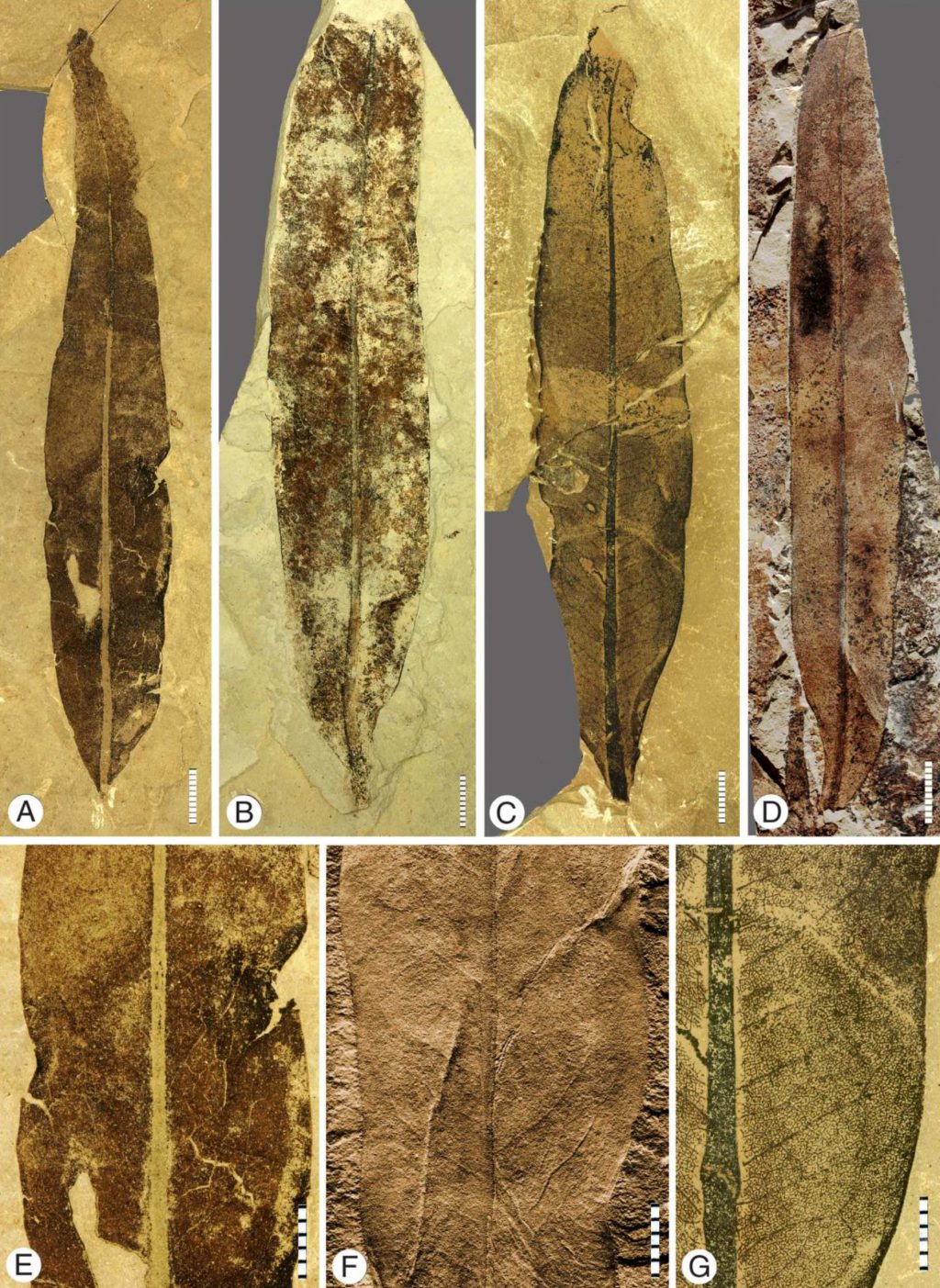

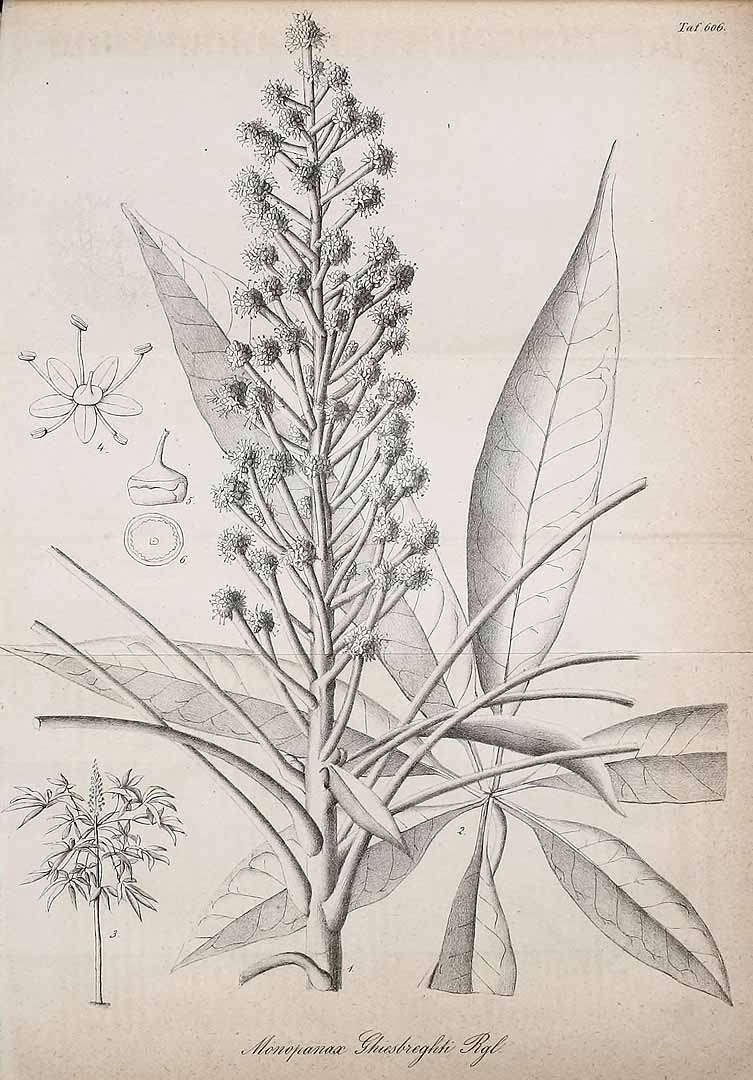

In 1969, fossilized leaves of the species Othniophyton elongatum — which translates to “alien plant” — were identified in eastern Utah. Initially, scientists theorized the extinct species may have belonged to the ginseng family (Araliaceae). However, a case once closed is now being revisited. New fossil specimens show that Othniophyton elongatum is even stranger than scientists first thought.

Steven Manchester, curator of paleobotany at the Florida Museum of Natural History, has studied 47-million-year-old fossils from Utah for several years. While visiting the University of California, Berkeley, paleobotany collection, he came across an unidentified and unusually well-preserved plant fossil collected from the same area as the leaves of Othniophyton elongatum.

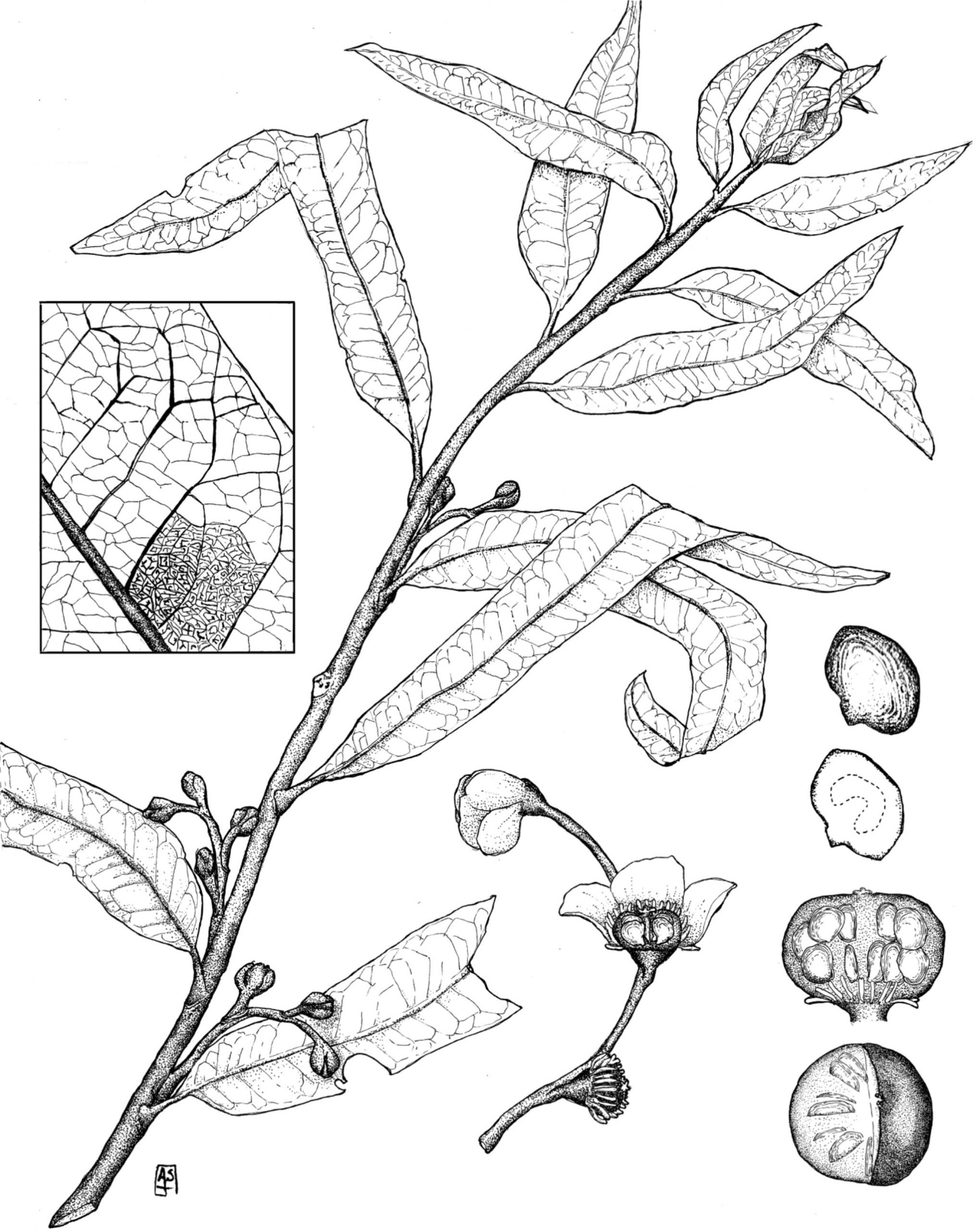

Manchester is the co-author of a new study in which he and his colleagues showed that the leaves in question belonged to a unique plant, with unusual flowers and fruits. Close observation revealed that the 1969 fossils and those later studied by Manchester at UC Berkeley were from the same plant species. But the leaves, fruits and flowers attached to the woody stem of the Berkeley fossils were nothing like those of the other plants in the ginseng family, to which that species had been originally assigned.

“This fossil is rare in having the twig with attached fruits and leaves. Usually those are found separately,” Manchester said.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

The authors extensively analyzed physical features of the old and new fossils, then methodically searched for any living plant family to which they could belong. There are over 400 diverse families of flowering plants alive today, but the authors couldn’t match the fossils’ strange assortment of features with any of them.

Resisting the urge to tidily lump the obscure specimen in with a living group, the team then searched for extinct families it might have belonged to but came up empty-handed once again.

The authors say their results underscore what may be a pervasive problem in paleobotany. In many cases, extinct plants that existed less than 65 million years ago are placed within modern families, or genera — the taxonomic groups directly above the level of individual species. This can create a skewed estimate of biodiversity in ancient ecosystems.

“There are many things for which we have good evidence to put in a modern family or genus, but you can’t always shoehorn these things,” Manchester said.

The species does not belong to any living family or genus

The fossils were discovered in the Green River Formation near the ghost town of Rainbow in eastern Utah. Roughly 47 million years ago, the area was a tectonically active, massive inland lake system that provided the perfect conditions for fossil preservation. Low-oxygen lake sediments and showers of volcanic ash slowed the decomposition of many fish, reptiles, birds, invertebrates and plants, allowing some of them to be preserved in amazing detail.

Researchers who had studied the original leaf fossils of this species had very little to work with. Without flowers, fruits or branches, they were limited to analyzing the shape and vein patterns of the leaves. Based on the arrangement, researchers thought it might be a single leaf made up of multiple smaller leaflets. This type of compound leaf is a defining feature of several plants in the ginseng family.

But the new fossils had leaves that were directly attached to stems, which painted a very different picture of what the plant once looked like.

“The two twigs we found show the same kind of leaf attached, but they’re not compound. They’re simple, which eliminates the possibility of it being anything in that family,” Manchester said.

The fossil’s berries ruled out families like the grasses and magnolias. The flowers did resemble some modern groups, but other features ruled those out, too. Even with such a pristine fossil in their repertoire, researchers were left with more questions than before.

Researchers could now see the fossil in a new light

Stumped, the team set the fossil aside for several years. Then the Florida Museum hired a curator of artificial intelligence who established a new microscopy workstation. When viewed through the digital microscope’s powerful lens and computer-enhanced shadow effect illumination, the authors could see subtle peculiarities they’d missed during prior observations.

When they focused on the fossil’s minute fruits, they could see micro-impressions left behind by their internal anatomy, including features of the small, developing seeds.

“Normally we don’t expect to see that preserved in these types of fossils, but maybe we’ve been overlooking it because our equipment didn’t pick up that kind of topographic relief,” Manchester said.

One of the plant’s strangest newly seen features was its stamens, the male reproductive organs of the flower. In most plant species, once the flower is fertilized, the stamens detach along with petals and the rest of the flower parts, which are no longer needed for reproduction.

“Usually, stamens will fall away as the fruit develops. And this thing seems unusual in that it’s retaining the stamens at the time it has mature fruits with seeds ready to disperse. We haven’t seen that in anything modern,” Manchester said.

With all modern families ruled out, they compared the traits to extinct families. Once again, there was no match to be found.

Julian Correa-Narvaez, the lead author of the study and a doctoral student at the University of Florida, played a major role in gathering information to identify the fossils. “It’s important because it gives us a little bit of a clue about how these organisms were evolving and adapting in different places,” he said.

Illustration by Manchester et al., 2024

Plant families can contain astonishing amounts of diversity. Seemingly disparate plants like poison ivy, cashews and mangoes are all in the same family, along with over 800 other species. It’s unclear how much diversity in this mysterious extinct group has been lost to time.

This isn’t the only enigmatic species that has come out of the Green River Formation. Similar situations have unfolded when plant fossils from the locality surprised researchers, leading to the discovery of other extinct groups. “The book published in 1969 has all these interesting mysteries that remain,” Manchester said.

With digital access to museum specimens through tools like iDigBio, researchers can continue to study and understand the natural history of plant evolution.

The article was published in the journal Annals of Botany.

Walter Judd of the Florida Museum of Natural History is also a co-author of the study.

Sources: Steven Manchester, steven@flmnh.ufl.edu;

Julian Correa-Narvaez, j.correanarvaez@ufl.edu

Media contact: Makena Lang, makenalang@ufl.edu