Bats, as the main predator of night-flying insects, create a selective pressure that has led many of their prey to evolve an early warning system of sorts: ears uniquely tuned to high-frequency bat echolocation. To date, scientists have found at least six orders of insects – including moths, beetles, crickets and grasshoppers – that have evolved ears capable of detecting ultrasound.

But tiger beetles take things a step further. When they hear a bat nearby, they respond with their own ultrasonic signal, and for the past 30 years, no one has known why.

“It’s such a foreign idea to humans: these animals flying around at night trying to catch each other in essentially complete darkness, using sound as their way of communicating,” said Harlan Gough, lead author on a new study that finally solves the mystery. While doing his doctoral research at the Florida Museum of Natural History, he reasoned that tiger beetles must receive a major benefit from making the sound, since it would also help bats locate them.

Tiger beetles are the only group of beetle scientists know of that seem to produce ultrasound in response to bat predation. An estimated 20% of moth species, however, are known to have this ability and provide a helpful reference for understanding the behavior in other insects. “This was a really fun study because we got to peel apart the story layer by layer,” Gough said.

The researchers began by confirming that tiger beetles produced ultrasound in response to bat predation. As bats fly through the night sky, they periodically send out ultrasonic pulses, which gives them snapshots of their surroundings. When a bat has located potential prey, they start clicking more frequently, allowing them to lock on to their targets.

This also creates a distinctive bat echolocation attack sequence, which researchers played for tiger beetles to see how they would respond. When a beetle flies, its hard shell opens to reveal two hindwings that generate lift. The elytra, which formerly covered the wings, are protective and don’t help with flight. These are typically held up and out of the way.

The researchers spent two summers in the deserts of southern Arizona and collected 20 different tiger beetle species to study. Of these, seven responded to bat attack sequences by swinging their elytra slightly toward the back. This caused the beating hind wings to strike the back edges of the elytra, like the two wing pairs were clapping. To a human’s ears it sounds like a faint buzzing, but a bat would pick up the higher frequencies and hear the beetle loud and clear.

“Responding to bat echolocation is a much less common ability than just being able to hear echolocation,” Gough said. “Most moths aren’t singing these sounds through their mouths, like we think of bats echolocating through their mouth and nose. Tiger moths, for example, use a specialized structure on the side of the body, so you need that structure to make ultrasound as well as ears to hear the bat.”

Tiger beetles were certainly responding to the sound of a bat attack with ultrasound. But why?

Some moths can jam bat sonar by producing several clicks in close, quick succession. The researchers quickly ruled out this possibility for tiger beetles, however, as they produce ultrasound that is too simple for such a feat.

Instead, they suspected that tiger beetles, which produce benzaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide as defensive chemicals, were using ultrasound to warn bats that they are noxious — like many moths do.

“These defensive compounds have been shown to be effective against some insect predators,” Gough said. “Some tiger beetles, when you hold them in your hand, you can actually smell some of those compounds that they are producing.”

They tested their theory by feeding 94 tiger beetles to big brown bats, which eat a wide array of insects but show a strong preference for beetles. To their surprise, 90 were completely eaten while two were only partially consumed, and just two were rejected, indicating that the beetles’ defensive chemicals do little to dissuade big brown bats.

According to Akito Kawahara, director of the museum’s McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, this was the first time scientists had tested whether tiger beetles were actually noxious to bats.

“Even if you identify a chemical, that doesn’t mean it’s a defense against a particular predator,” Kawahara said. “You don’t actually know until you do the experiment with the predator.”

It turned out tiger beetles don’t use ultrasound to warn bats of their noxiousness. But there was one last possibility. Some moths produce anti-bat ultrasound even though they are palatable. Scientists believe these moths are trying to trick bats by acoustically mimicking the ultrasonic signals of genuinely noxious moth species.

Could tiger beetles be doing something similar? The researchers compared recordings of tiger beetle ultrasound, collected earlier in the study, with recordings of tiger moths already in their database. Upon analyzing the ultrasonic signals, they found a clear overlap and the answer to their question.

Tiger beetles, which do not have chemical defenses against bats, produce ultrasound to mimic tiger moths, which are noxious to bats.

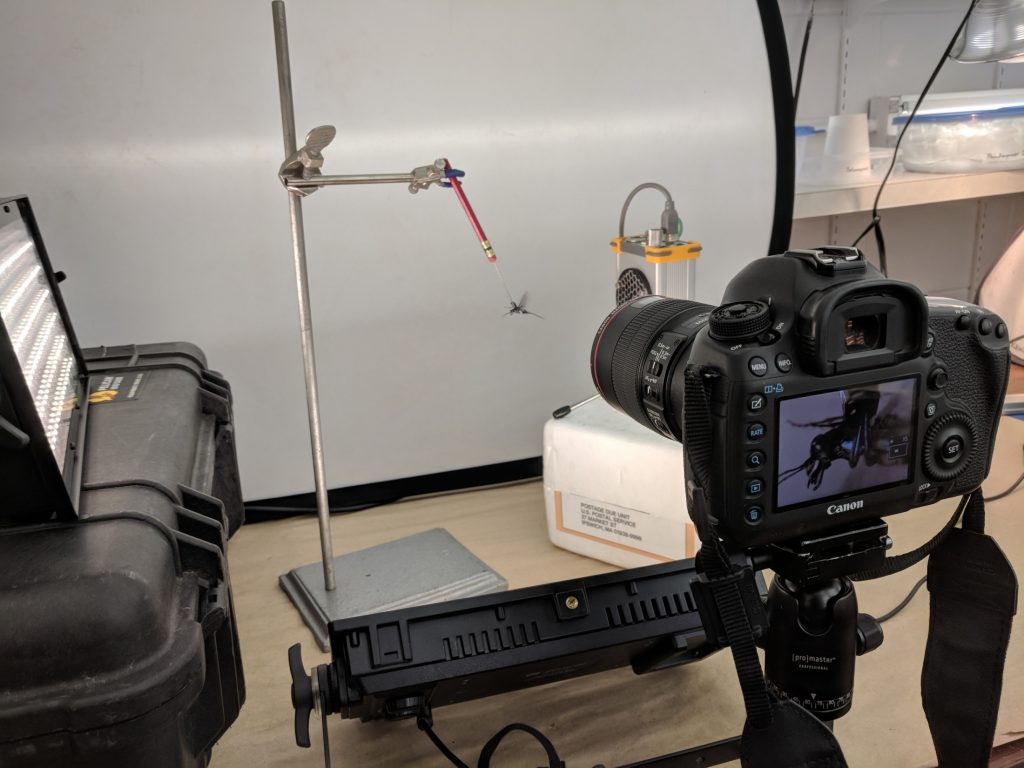

Photo courtesy of Geena Hill.

But this behavior is limited to tiger beetles that fly at night. Some of the 2,000 species of tiger beetles are active exclusively during the day, using their vision to chase and hunt smaller insects, and don’t have the selective pressure of bat predation. The 12 diurnal tiger beetle species that the researchers included in the study are evidence of this.

“If you get one of those tiger beetles that goes to sleep at night and play bat echolocation to it, it makes no response at all,” Gough said. “And they seem to be able to pretty quickly lose the ability to be afraid of bat echolocation.”

Researchers suspect there may be even more undiscovered examples of ultrasonic mimicry, given how understudied the acoustics of the night sky are.

“I think it’s happening all over the world,” Kawahara said. “With my colleague, Jesse Barber, we have been studying this together for many years. We think it’s not just tiger beetles and moths. It appears to be happening with all kinds of different nocturnal insects, and we just don’t know simply because we haven’t been testing in this manner.”

These delicate ecological interactions are also at risk of being disrupted soon. Acoustic mimicry needs a quiet environment to work, but human impacts like noise and light pollution are already altering what the night sky looks and sounds like.

“If we want to understand these processes, we need to do it now,” Kawahara said. “There are amazing processes taking place in our backyards that we can’t see. But by making our world louder, brighter and changing the temperature, these balances can break.”

The authors published their study in the journal Biology Letters.

Juliette Rubin, former graduate student at the University of Florida and Jesse Barber of Boise State University were also authors on the study.

This study was funded by the National Science Foundation (grant Nos. IOS-1121739, IOS-1920895, IOS-1920936 and IOS-1121807).

Sources: Harlan Gough, harlan.gough@gmail.com;

Akito Kawahara, kawahara@flmnh.ufl.edu

Writer: Jiayu Liang, jiayu.liang@floridamuseum.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452