Photo by Jeff Gage

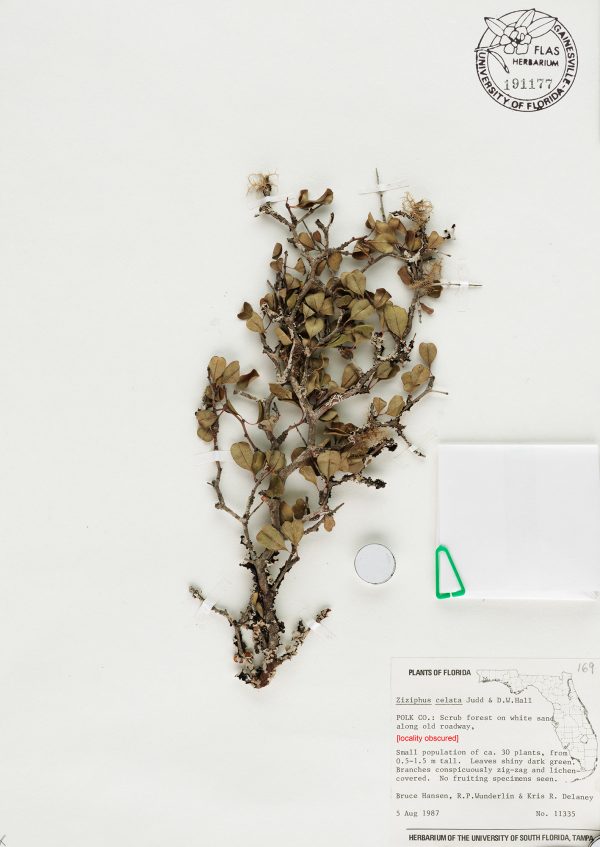

In 1947, a small package containing an unknown plant specimen arrived at the Florida Museum of Natural History Herbarium. For 37 years, the thorny stem and leaves sat pressed between pages of a yellowed newspaper, filed in a cabinet among the vast library of Florida plants, until University of Florida botanist Walter Judd encountered the specimen in 1984. Knowing it was from the Lake Wales Ridge in central Florida, Judd and herbarium curator David Hall traveled to the area in search of wild populations, but returned to Gainesville empty-handed. Pronouncing it extinct, they published a paper naming the mysterious plant Ziziphus celata.

“Celata means hidden, because the plant was hiding from us,” Judd said. “We searched every little scrub patch that we found, but we didn’t see it – we were hoping that this would kind of be like the pebble that gets the avalanche rolling, and soon enough, there was an article written about the plant in the local newspaper.”

The media attention attracted amateur botanists and collectors to the field, and three years later, native populations of Ziziphus celata were re-discovered. But the excitement was short-lived, as researchers soon learned the species was self-incompatible, meaning two different plants are needed to produce seeds.

In 2007, the tide turned again when additional populations were found, and recent research on the plants revealed they have some genetic diversity, giving new hope to the 15-year effort to re-establish one of the state’s most rare and endangered plants.

“We were pretty excited that they found those new populations, and it’s surprising because they weren’t far from were the previous populations were found – people had looked in that area but they hadn’t been seen before,” said Florida Museum researcher Matthew Gitzendanner, lead author of a study genotyping the plants, published in the February 2012 issue of Conservation Genetics. “And then it was even more exciting when we started finding genetic variation because all the previous populations had each been a single clone.”

A shrubby species with small leaves and thorny branches, Ziziphus celata, also known as Florida ziziphus, grows to about 6 feet tall then spreads outward. It loses its leaves during the winter, and when it flowers around January, hundreds of tiny blossoms cover the branches so the whole plant appears yellowish-green, Gitzendanner said. With its limited geographic distribution, genetic restrictions and general inability to reproduce sexually, the shrub’s genetic data could provide the information necessary to reintroduce wild populations.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

“There’s only 14 populations in the wild, and unfortunately, only a couple of those are actually are on protected lands,” Gitzendanner said. “The masterpiece populations that have the genetic diversity are on private property and unprotected, so the landowners can do whatever they want with them.”

Protected under the Endangered Species Act, Florida ziziphus also provides a habitat for the endangered Florida Scrub Jay, among other animals endemic to the area. Largely lost due to crop production and urbanization, the uses of the plant are unknown because of its rarity. But its close relative native to Southeast Asia, Ziziphus ziziphus, or jujube, has been cultivated in China as food and medicine for thousands of years, and the genetic data indicates it was likely more widespread at one point, Gitzendanner said.

“There are about 30 plant species endemic to only the ridge and unfortunately about 90 percent of the habitat has been affected by agricultural and urban development,” Gitzendanner said. “Most of the species found there are rare and of conservation concern.”

Since 2002, Florida Museum and Archbold Biological Station researchers have worked together to save and re-establish Florida ziziphus populations, with hopes of restoring a more sustainable ecosystem of native plants.

The Lake Wales Ridge represents central Florida’s highest land elevation. It spans about 100 miles and is known as the oldest ecosystem in the Southeast, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service website. Its sand hills are home to many plants and animals found nowhere else.

“Because it’s so dry and lightning is very common, it’s a habitat that historically had frequent fires, so many of the plants are adapted to that,” Gitzendanner said. “But because of changes to the habitat and lack of wildfires caused by urbanization, other plants have taken over, such as oak trees.”

Some Florida ziziphus plants of mixed genotypes have been established at Bok Tower Gardens in Lake Wales, which serves as a genetic repository, but researchers hope the new genetic information will enable establishment of self-sustaining populations.

And it all started with a specimen in the Florida Museum’s collection.

“We figured naming this specimen got the ball going – you have to know something exists before you go looking for it,” Judd said. “And this was a plant stored in the Herbarium for decades.”

For more information about Ziziphus celata research at Archbold Biological Station, please visit www.archbold-station.org/station/html/research/plant/zizcelsppacc.html.

Learn more about the Herbarium at the Florida Museum.

Learn more about the Molecular Systematics & Evolutionary Genetics Lab at the Florida Museum.