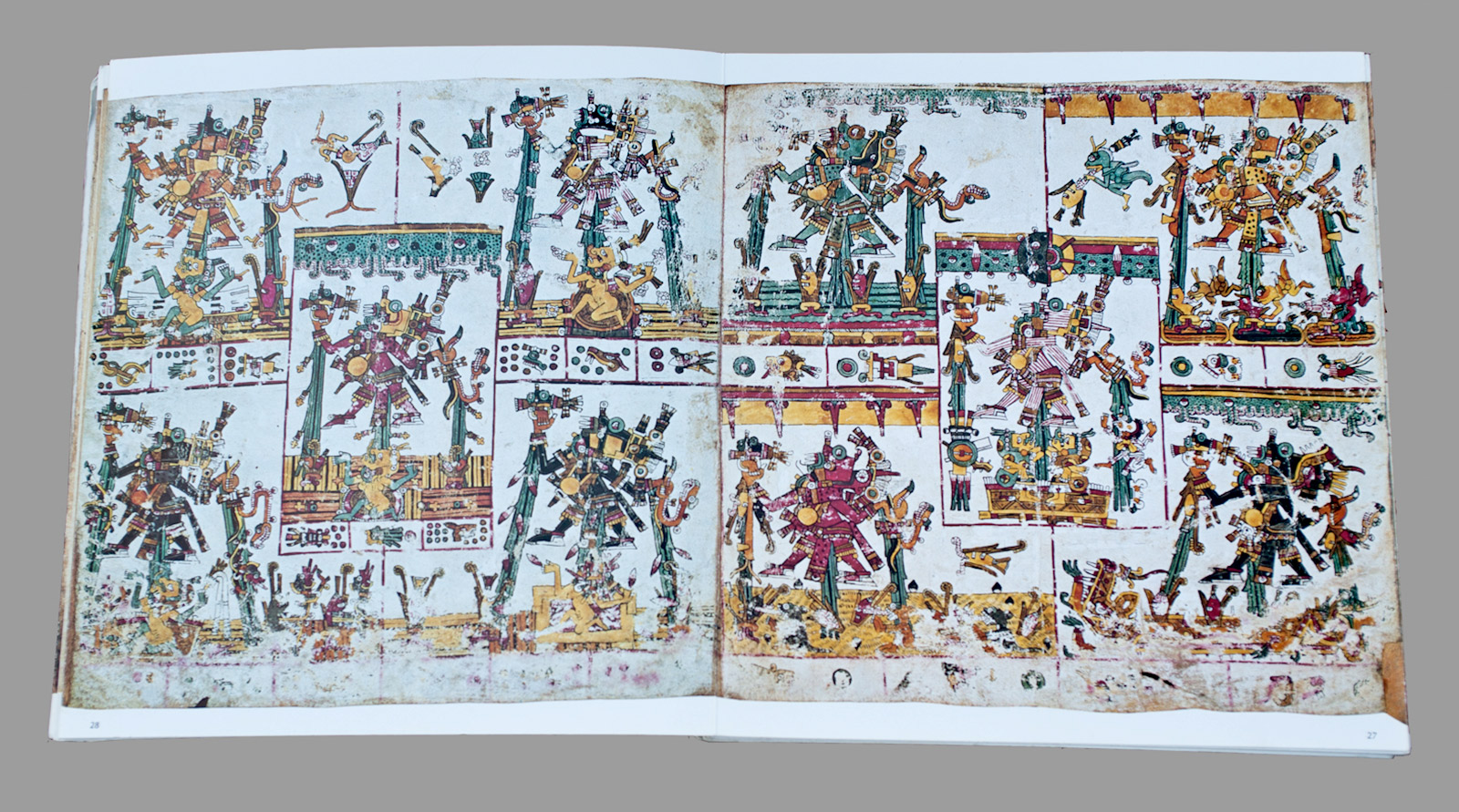

The events were depicted in ancient Mesoamerican codex

In ancient Mesoamerica, as the Aztec calendar predicted the end of the world with a total solar eclipse followed by a cataclysmic earthquake, neighboring cultures also looked to the heavens for signs of their future.

Their painted books depicted solar eclipses, comets and other celestial patterns, for the skies brought good fortune or bad, a successful crop season or dreaded famine.

Predictions and records of climate cycles appear in the Codex Borgia, the finest of the five Borgia group manuscripts to survive the Spanish conquest of the Aztec in 1521. Many scholars over the last few centuries have offered interpretations of events documented in the Codex Borgia, a 76-page screen-fold book made of deerskin, but they had not taken into account its origin in Tlaxcala and notation of real events.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

New research using tree-ring data to match climate events described in the codex shows dates that may be deciphered using the Aztec calendar.

“Mesoamerica is a single cultural area and the calendar works similarly — many of the deities are the same, but unless we establish who made this codex definitively, we can’t talk about anything,” said Florida Museum of Natural History Curator of Latin American Art and Architecture Susan Milbrath. “Initially, Aztec sources were used to interpret it, then the Mixtec scholars around the 1960s started to claim it. Now, with the work of Tony Aveni and this study, we can definitively say it was Tlaxcaltec, but it’s taken about 40 years for it to get pulled back into the Aztec dialogue.”

In a study published Oct. 5, 2011, in Ancient Mesoamerica, Milbrath and Chris Woolley, a University of Florida history graduate student, used tree-ring data extrapolated from Douglas fir in Puebla, Mexico, to show the Codex Borgia reflects Tlaxcaltec records. The study focuses on pages 27 and 28 of the Borgia, which feature a central illustration of Tlaloc, the Postclassical period central Mexican rain god, surrounded by imagery of the planting season.

“These are like farmer’s almanacs and I think this is fascinating because we don’t have consistent climate data in the United States prior to the Civil War, as far as humans recording climate events,” Milbrath said. “Up until recently, these almanacs were looked at as fortune-telling, yet they actually record real dates correlating with weather patterns, such as in 1467, which corresponds to One Reed and One Crocodile on Borgia 27 in a scene with abundant rain and a bountiful maize (corn) crop.”

This almanac and the one on page 28 show a variety of weather conditions that can be correlated with tree-ring records. During times of drought, trees are unable to grow at their normal rate, so the width of the rings were compared with the calendar year and its accompanying images, which range from dry land riddled with rodents to star-and circle-speckled worms.

“An entomologist at UF recognized a caterpillar called the fall army worm based on the raised bumps on their skin,” Milbrath said. “The stars painted on these caterpillars are appropriate because they will become moths that are nocturnal. The caterpillars attack maize especially toward the end of the growth stage, and by that time, they’re burrowing sideways into it and they destroy the cob — they don’t eat the whole cob, but they ruin it.”

Milbrath has spent many years interpreting the Codex Borgia, incorporating astronomical events, cultural history and agricultural cycles to draw a picture of life in central Mexico before the Spanish Conquest. By reconstructing 15th-century paleoclimate events, she hopes the research may also be applied to understand long-term agricultural patterns in relation to variable weather and climate changes.

“This codex also shows events in 1496, the year of the only total solar eclipse seen in the post-classic period, and seasonal plants and animals in relation to weather patterns in that year, providing another form of natural history record,” Milbrath said. “The tree ring dates are real and can be compared with the records in the Codex Borgia, but this is just a starting point. Ultimately, I’d like to find out if the Mesoamericans were good natural historians.”

Mysterious appearance

Named after the Italian Cardinal Stefano Borgia, the Codex Borgia was discovered in Italy in the 1800s. According to legend, Cardinal Borgia rescued the 35-foot document from being burned by the neighbor’s children.

“This is pre-Columbian — there was not a single bit of evidence that the Spaniards had arrived in the paintings,” Milbrath said. “The Codex Borgia was something they took back to Europe with them, and it ended up in Europe very early, but it’s kind of mysterious how it ended up in Italy. There are two codices that Cortez took back, and this is possibly one of the two.”

When Hernan Cortez first arrived in central Mexico, the Tlaxcaltecs were willing to help him because they were surrounded by their enemies, the Aztecs, she said.

“The Tlaxcalans ended up collaborating with the Spaniards, so I think this codex was a gift to the Spaniards because they were on good terms. We don’t have any Aztec pre-Colombian codices — they were all destroyed by the Spaniards, but this codex was probably preserved because the Tlaxcaltecs were their allies.”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

While Milbrath’s research alters the basis for interpreting the codex, the painted symbols, like Bible stories, will always be up for interpretation. Even seemingly obvious characters stand a test of hundreds of years’ time. Today, new methods can be applied to the analysis, using natural history records that can be correlated with “real-time events” in the codex.

“Growing up, I thought locusts were related to drought, but they actually need some moisture to breed,” Milbrath said. “When they are running out of food, they become more aggressive so they form swarms. These swarms appear in the Codex Borgia in a scene that shows a puddle of drying water with a sunny sky overhead, unlike most other scenes showing rainy skies.”

The tree-ring records for that year show early rains followed by dry conditions, an ideal situation for forming swarms of locusts.

“If you didn’t know this codex the way we do now, you might think it is just predictions,” she said. “You can read and re-read these symbolically charged images and come to a new understanding of how the people of ancient Mexico viewed the world of nature.”