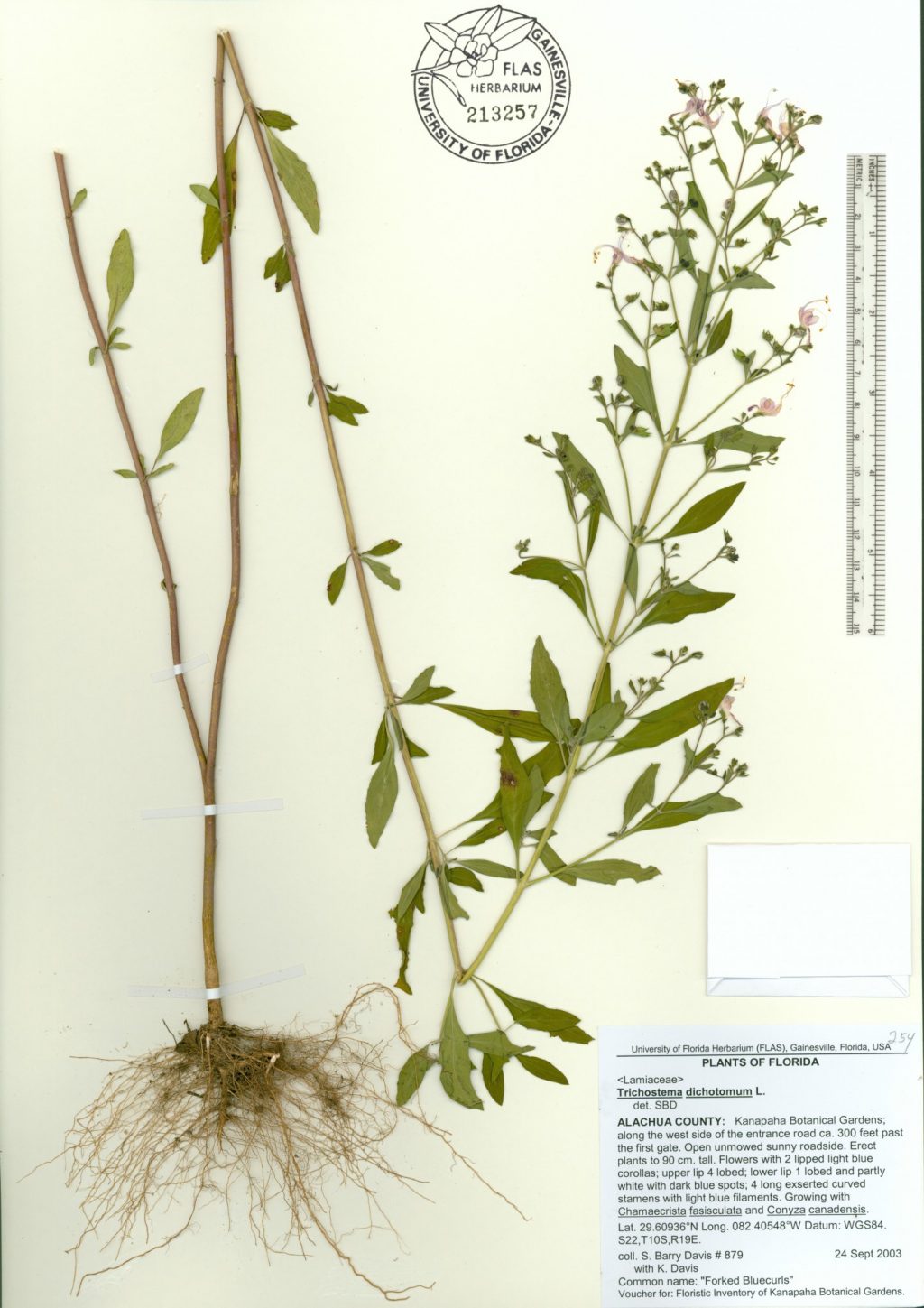

Botanist Mark Whitten was rummaging in an old drawer in the University of Florida Herbarium for tracing paper when he discovered something unexpected: hundreds of World War II-era watercolor paintings, each of a unique Florida plant.

Likely untouched in the 20 years since the herbarium’s move into Dickinson Hall, the collection was largely forgotten, but the same cool, dark conditions intended to preserve the herbarium’s more than 400,000 specimens also preserved the paintings.

Artist Minna Fernald donated over 320 paintings of Florida wildflowers to the university in 1942, providing a rich record of the state’s past ecological life.

“If you go out looking for these plants nowadays, you can find them but they’re only in little isolated preserves,” said Whitten, a biological scientist at the herbarium. “My impression is what Minna Fernald saw was a much more wild and interesting Florida than what it is now.”

In fact, Whitten has no doubt that Fernald spent a great deal of her time in the field.

“The way she captured the essence of the plants, it was clear to me that she wasn’t just sitting in her parlor with a vase full of things that people had brought her,” he said.

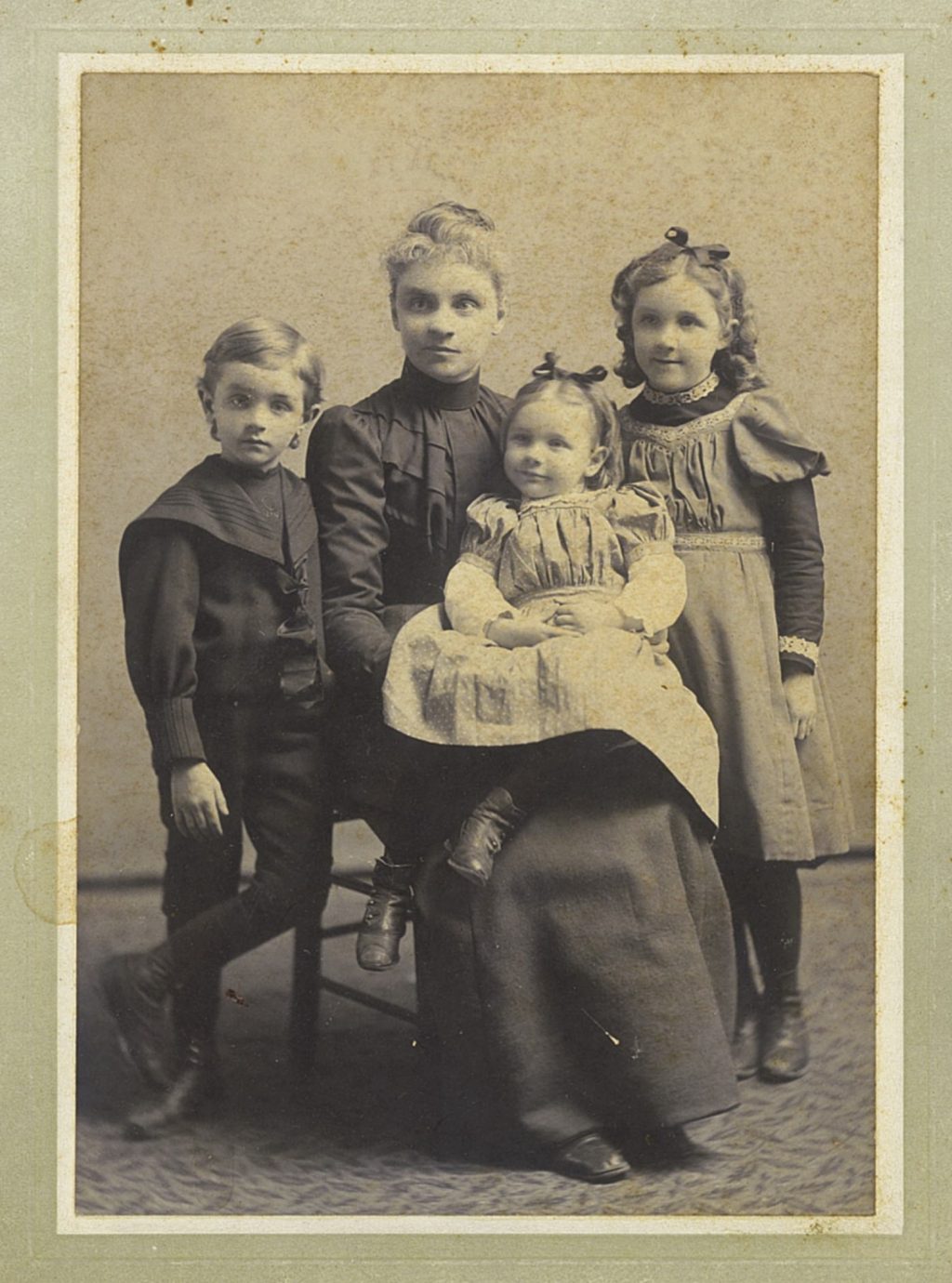

Considering Fernald’s history, it’s likely that her work was indeed done in nature. Married to the chair of the department of entomology at the University of Massachusetts, Fernald spent much of her life in Massachusetts before moving to Winter Park to retire.

Photo courtesy of Nancy Fernald

While in Florida, her husband was honored for his contributions to the field with a banquet by the Newell Entomological Society at UF. According to the program, the dinner included speeches by Harold Hume, Jon Tigert and Wilmon Newell – all familiar names at the university today and important figures in the history of the Florida Agricultural Experiment Station that first housed the herbarium.

Herbarium employees cannot say for sure why Fernald chose to donate her collection.

Fernald’s obituary in The Winter Park Herald attributes the skill and fine detail found in the paintings to her studies at the Maryland Institute under Hugh Newell of the American Watercolor Society, whose work was popular during the mid-19th century. The Herald says that Fernald’s own art was exhibited in Amherst, Massachusetts, and later won many awards in the Central Florida Exposition and exhibitions of the Florida Federation of Art.

The most impressive thing about Fernald’s paintings is that the plants she chose to depict are nearly all immediately identifiable, said Lucas Majure, assistant curator of the herbarium, which is part of the Florida Museum of Natural History.

“Not only are they of artistic value, but I would say they’re of scientific value from the standpoint that we were all standing around those paintings going ‘Oh, that’s that, that’s that,’ because they’re exquisitely painted,” he said. “They’re really nice paintings, but at the same time, they’re very realistic.”

The colors of herbarium specimens inevitably fade, but Fernald’s paintings capture the beauty that first catches a collector’s eye in the field.

Fernald’s artistic legacy lives on in her great-granddaughter Nancy Fernald. An artist in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, Nancy Fernald said she knew she wanted to be a painter when she was 5 years old and heard about her great-grandmother’s lost wildflower collection from her mother. Fernald said she’s happy that her great-grandmother is garnering more attention.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

“Doing research on Minna and my grandmothers, I found so much information about the men, and I thought, ‘I would really like to know more about the women,’” she said.

Fernald said she is considering a trip to Florida to see the paintings.

“I’m so delighted, partly because I wanted to know about the paintings, and also because I’m so pleased that Minna’s work is being recognized,” she said.

Fernald has several handwritten memoirs that she feels make her even more closely connected to her great-grandmother. Minna Fernald is said to have taken a sketchbook and notebook with her on all of her travels, and her work centered mainly on landscapes and wildflowers.

The university plans to digitize the paintings to preserve them and offer them a wider audience.

“I want people who see these to sort of get a sense of the beauty of the natural world, to learn more about somebody that took great care to paint these things for us,” said Valrie Minson, UF Chair of Marston Science Library and agricultural librarian, who has taken the lead on digitizing the paintings. She hopes that the paintings will provide context for what the university’s libraries have to offer. “It’s a way of showing people what you can do with library collections.”

Minson said that she’s glad to highlight female artists because “it’s something we don’t hear enough about.”

The Florida Museum is saddened by Mark Whitten’s passing. Read his eulogy here.

Sources: Lucas Majure, lmajure@floridamuseum.ufl.edu, 352-273-2102;

Valrie Minson, vdavis@uflib.ufl.edu, 352-273-2880

Learn more about the University of Florida Herbarium at the Florida Museum.

Browse the Minna R. Fernald Collection of Paintings of Florida Wildflowers on the University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries site:

Browse paintings