The mighty Calusa ruled South Florida for centuries, wielding military power, trading and collecting tribute along routes that sprawled hundreds of miles, creating shell islands, erecting enormous buildings and dredging canals wider than some highways. Unlike the Aztecs, Maya and Inca, who built their empires with the help of agriculture, the Calusa kingdom was founded on fishing.

But like other expansive cultures, the Calusa would have needed a surplus of food to underwrite their large-scale construction projects. This presented an archaeological puzzle: How could this coastal kingdom keep fish from spoiling in the subtropics?

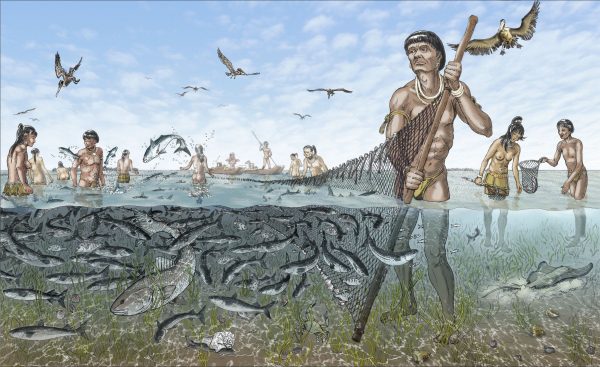

A new study points to massive structures known as watercourts as the answer. Built on a foundation of oyster shells, these roughly rectangular enclosures walled off portions of estuary and likely served as short-term holding pens for fish before they were eaten, smoked or dried. The largest of these structures is about 36,000 square feet – more than seven times bigger than an NBA basketball court – with a berm of shell and sediment about 3 feet high. Engineering the courts required an intimate understanding of daily and seasonal tides, hydrology and the biology of various species of fish, researchers said.

The watercourts help explain how the Calusa could rely primarily on the sea.

“What makes the Calusa different is that most other societies that achieve this level of complexity and power are principally farming cultures,” said William Marquardt, curator emeritus of South Florida Archaeology and Ethnography at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “For a long time, societies that relied on fishing, hunting and gathering were assumed to be less advanced. But our work over the past 35 years has shown the Calusa developed a politically complex society with sophisticated architecture, religion, a military, specialists, long-distance trade and social ranking – all without being farmers.”

Florida Museum illustration by Merald Clark

The fact that the Calusa were fishers, not farmers, created tension between them and the Spaniards, who arrived in Florida during the 16th century when the Calusa kingdom was at its zenith, said study lead author Victor Thompson, director of the University of Georgia’s Laboratory of Archaeology.

“The Spanish soldiers, priests and officers were used to dealing with agriculturalists, such as the people they colonized in the Caribbean who grew maize surpluses for them,” Thompson said. “This would not have been possible with the Calusa. In fact, in a late 1600s mission attempt by the Franciscans, hoes were unloaded off the ship, and when the Calusa saw this, they remarked, ‘Why didn’t they also bring slaves to till the ground?’”

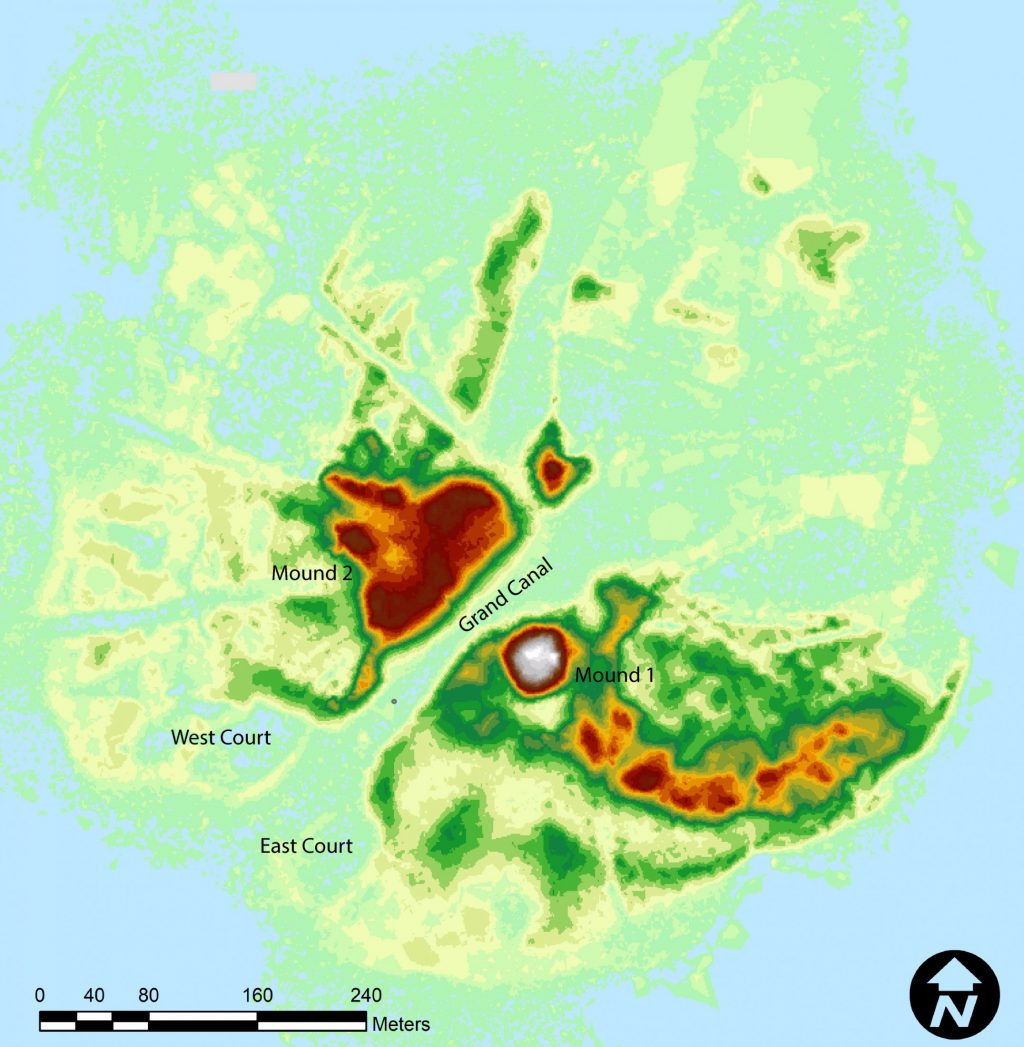

Thompson, Marquardt and colleagues analyzed two watercourts along the southwest shore of Mound Key, an island in Estero Bay off Florida’s Gulf Coast and the seat of Calusa power for about 500 years.

These courts, still visible today, flank the grand canal, a marine highway nearly 2,000 feet long and averaging 100 feet wide, which bisects the key. Both have yards-long openings in the berms along the canal, possibly to allow Calusa to drive fish into the enclosures, which could then be closed with a gate or net.

The team studied the watercourts and surrounding areas using remote sensors, cores of sediment and shell and excavations. The bisected key features two large shell mounds, one on either side of the island. Remote sensing showed slopes leading from the watercourts to the top of the mounds, which may have been causeways for transporting food. On the shoreline, researchers found evidence of burning and small post molds, possibly for racks used to smoke and dry fish.

Radiocarbon dating suggests the watercourts were built between A.D. 1300 and 1400 – around the end of a second phase in the construction of a king’s manor, an impressive structure that would eventually hold 2,000 people, according to Spanish documents.

Florida Museum illustration by Merald Clark

A.D. 1250 also corresponds to a drop in sea level, which “may have impacted fish populations enough to help inspire some engineering innovation,” said Karen Walker, Florida Museum collection manager of South Florida Archaeology and Ethnography.

Fish bones and scales found in the western watercourt show the Calusa were capturing mullet and likely pinfish and herring, all schooling species. Florida Gulf Coast University geologist Michael Savarese’s analysis of watercourt core samples revealed dark gray sediment that was rich in organic material, suggesting poor circulation. High tide would have refreshed the water to some extent, Marquardt said.

“We can’t know exactly how the courts worked, but our gut feeling is that storage would have been short-term – on the order of hours to a few days, not for months at a time,” he said.

While researchers previously hypothesized watercourts were designed to hold fish, this is the first attempt to study the structures systematically, including when they were built and how that timing correlates with other Calusa construction projects, Marquardt said.

The Calusa dramatically shaped their natural environment, but the reverse was also true, Thompson said.

“The fact that the Calusa obtained much of their food from the estuaries structured almost every aspect of their lives,” he said. “Even today, people who live along coasts are a little different, and their lives continue to be influenced by the water – be it in the food they eat or the storms that roll in on summer afternoons in Southwest Florida.”

The study will publish this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Funding for the research was provided by the National Geographic Society, the John S. and James L. Knight Endowment for South Florida Archaeology and the National Science Foundation.

Sources: William Marquardt, bilmarq@flmnh.ufl.edu;

Victor Thompson, vdthom@uga.edu;

Karen Walker, kwalker@flmnh.ufl.edu