University of Florida researchers are taking down the Plexiglas walls between museum collections and K-12 classrooms with an educational program that uses 3-D printed fossils and hands-on lessons to spark young learners’ interest in science, technology, engineering and math.

Known as iDigFossils, the program offers curriculum on complex subjects such as evolution and climate change, taught with the help of printable fossil replicas from the Florida Museum of Natural History’s digital collections, including bones from three-toed horses, giant ground sloths and megalodon, the world’s largest shark.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

The interactive lessons encourage students to flex the mental muscles that real-world scientists use — curiosity, skepticism and inquiry — and engage learners who might not think of themselves as the “science type,” said Claudia Grant, Florida Museum doctoral student and iDigFossils project coordinator.

“One of the advantages of using this approach is that we can engage kids who are totally uninterested in science or who often get left behind in traditional STEM classes,” said Grant, who remembers struggling with science in high school. “These lessons help show kids that don’t consider themselves ‘science people’ that their skills are still important. When you see how this works in the classroom, it’s compelling.”

Equipping tomorrow’s scientists

Training the next generation of scientists and engineers is crucial to tackling global challenges such as climate change and food and energy security, Grant said. But students in the U.S. tend to lag behind their peers in other countries in science literacy and proficiency. New educational reform initiatives, such as Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and Common Core State Standards (CCSS), aim to close the gap, but meeting the initiatives’ criteria for cross-discipline learning has been a challenge for teachers, as the majority of curricula present STEM disciplines separately.

“Science is a collaborative, multidisciplinary process, and it should be taught that way,” Grant said. “Crossing disciplines can be tough, so we wanted to create curriculum that would empower teachers to do that while teaching the topics they need to teach and meeting NGSS and CCSS objectives.”

Researchers from the museum, principal investigator Pasha Antonenko of the College of Education, Victor Perez of the department of geological sciences, Corey Toler-Franklin of the department of computer and information science and engineering and Aaron Wood from Iowa State University worked with K-12 teachers to design creative, brain-stimulating activities. The lessons draw from the museum’s digitized collections, mimic real research and integrate principles from all four STEM disciplines, in line with NGSS and CCSS objectives.

Paleontology acts as “gateway science”

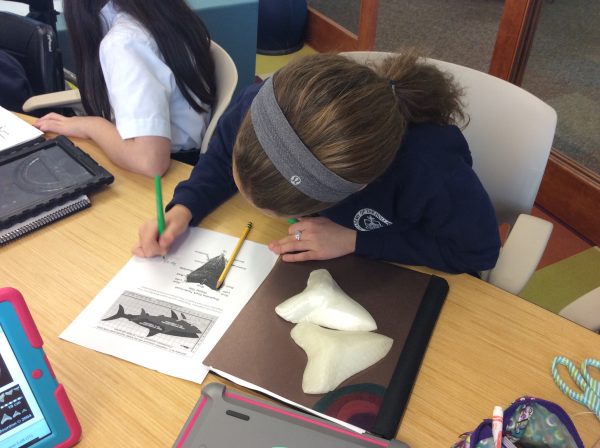

Printed fossil replicas also buck a hallmark museum rule: Look, but don’t touch.

“This is revolutionizing how kids interact with fossils by enabling them to have hands-on experiences with specimens they otherwise wouldn’t have access to,” said Bruce MacFadden, distinguished professor and curator of vertebrate paleontology and co-principal investigator of iDigFossils. “Whether you’re in Fargo, North Dakota, or Timbuktu, you can download lessons and fossils from the web. This takes the museum straight into the classroom.”

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

He said paleontology is a model for the cross-disciplinary thinking encouraged by NGSS and CCSS because it integrates concepts from multiple disciplines, including biology, environmental science, geology, oceanography and anthropology. It’s also a natural “gateway science” for students.

“Paleontology is instantly charismatic,” he said. “Kids love giant snakes, shark teeth and dinosaurs.”

Study shows iDigFossils shark lesson increases student engagement

The iDigFossils team recently published a case study of the program’s effectiveness, based on a pilot lesson in which students explored principles of math and evolution with the help of megalodon, an ancient shark that could dispatch a whale.

Students at middle and high schools in Florida and California printed a set of 46 megalodon teeth from scans of real fossils and used them to investigate two questions: How can fossil teeth reveal a shark’s total body length, and how do scientists use modern sharks to understand sharks like megalodon, which dominated the oceans 23 to 2.6 million years ago?

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

They measured the teeth and used equations based on the relationship between tooth crown height and the body length of great white sharks — often used as proxies for megalodon — to estimate the shark’s length.

Since all the teeth come from the same fossil shark, estimates of body length should have been similar. Instead, students found that their estimates varied widely. They discovered the problem lay in the equations themselves: Equations based on great white sharks’ tooth crown height do not yield accurate estimates of megalodon’s body length.

“Kids have the opportunity to have that ‘Aha!’ moment that scientists have,” Grant said.

A survey of 26 students who completed the megalodon lesson showed nearly 74 percent agreed the hands-on activities were an effective method of instruction.

One student wrote, “Having access to a 3-D printer allowed us to grasp things differently. Being able to physically hold something in your hand … is definitely very engaging. I have never been to a science class where everyone was so engaged with what was going on.”

Photo courtesy of Megan Higbee Hendrickson

Teachers also reported an increase in students’ enthusiasm as a result of using 3-D fossils in the classroom.

“Using real and 3-D printed fossils allows me to put a piece of the past into the hands of the students,” said Megan Higbee Hendrickson, a teacher at the Academy of the Holy Names in Tampa. “These collaborations (with UF scientists) and the fossils I have access to have transformed the way we think of STEM in my classroom. The problem-solving and engineering skills that the students used to design and construct (megalodon’s) jaw would have been impossible to recreate using a textbook or video.”

An advantage of the group activities is that students learn they do not need to excel in every skill to be a scientist, Grant said.

“In the real world, a scientist doesn’t need to be an expert at everything — where you have a weakness, that’s when you recruit a collaborator with a corresponding strength,” she said.

Lesson plans and instructor notes are available at www.paleoteach.org, and 3-D files can be downloaded from www.morphosource.org.

The researchers published an assessment of their pilot lesson plan in “Paleontological Society Special Publications.” The study is available at https://doi.org/10.1017/scs.2017.15.

The National Science Foundation and Duke University provided support for the project and research.

Learn more about the Vertebrate Paleontology Collection at the Florida Museum.