How does someone do field science in the age of COVID-19? Your guess is as good as mine. After waiting for more than a year to get outside, the opportunity came in late spring this year at UF’s IFAS Cedar Key Nature Coast Biological Station. Our goals were to tag ten or more baby bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) in an effort to document a local nursery habitat, to test new equipment, and learn the skills necessary for an upcoming month-long research trip (stay tuned for a blog on this adventure). We can better understand sharks’ life histories and make more informed conservation regulations by documenting these nurseries. Unfortunately, due to the threat of COVID, I couldn’t bring any undergrad students to assist me. With no other help available, I turned to my most trusted partner, my fiancé. She is a scientist but not a field biologist and did not have experience working on boats. So, with much to learn, a novice but loving crew, and a tiny boat, we set out to our remote field station on Sea horse Key, where we would spend the following week. Seahorse Key is part of the Cedar Key National Wildlife Refuge, which was established in 1929. The University of Florida began using the area as a marine laboratory in 1952. Today the lighthouse is the oldest on Florida’s west coast.

Sea Horse Key is known for two things; birds and snakes that eat birds. Mysteriously, years ago, the birds relocated, leaving just the venomous snakes and a lighthouse dormitory where we would stay. The first hurdle would be getting there. We had been in quarantine for 14 months at this point, only venturing out for the occasional hike. I hadn’t even seen our boat in two years and had never piloted it alone. So that first morning, I was a nervous wreck. The sun was just coming up, the sea air was moist, and the heat was just beginning to warm the boat ramp. By the time I had the boat in the water and loaded with all the gear, the sun was blinding, starting to cook my pale Irish skin, and the pelicans that followed us up and down the pier had learned some colorful language. Our boat was an 18ft Hell’s Bay flats skiff, a fine boat but lacking in space. The entire boat ramped seemed to stare in fascination as I piled our equipment, food, and personal gear on the tiny vessel. No doubt wondering what we were doing and if our boat would continue to float once I finished. Before pushing off, I was told by my better half to sit down, shut up, and rehydrate. It was not even lunch, and I was already in trouble.

Having chugged a drink and receiving clearance to proceed from the boss, we pushed off and puttered along out of the harbor. The water was calm, and the sun was just getting hotter. After a 20-minute ride, we had reached the edge of the island only to hit a sand bar. The engine shut off, and I repeatedly tried to restart it. Embarrassed and angry, I swallowed my pride and called for help. With 30 minutes to wait until assistance arrived, I slipped off my boots and slid into the cool water. Figuring I could pull us to the island’s dock, I slowly guided our craft into the mangroves. Help arrived in the form of the Island caretaker, who informed me I had to be 10% smarter than the stuff I was working with. After putting the boat in neutral, the engine started just fine *sigh*.

The island hadn’t seen visitors since the start of COVID. The grass was thick, and the forest encroached on the edges of the cleared paths. We hauled our gear up the steep hill to the lighthouse, carefully checking for the island’s venomous residents along our path. White egrets called after us, either welcoming or cursing our arrival. The house had long porches in the front and back, with white paint showing its time in the elements. Screen doors lined the porches every 6-8 ft, allowing anyone to step outside from any room or allow airflow in the heat. The tin roof was clean and shined in the sun. Several chimneys shot up from the roof with cacti growing in them, and in the center, the tall light tower. For a field station, it was a paradise. Having slept in grass huts and half-open shelters in remote locations, I felt spoiled to have this building to live in; my sterile lab-based partner was less impressed.

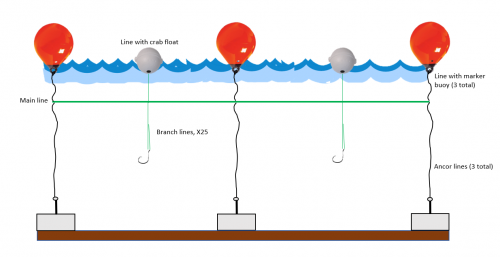

Before dinner that first night we set out to look at our field site. The almost hour-long commute into the open Gulf was a bit of a bumpy ride, but we made it to our site at the mouth of the Suwannee River. The salt marsh there is a transitional habitat between the saltwater of the Gulf of Mexico and the river’s freshwater. It makes a good nursery for many animals, including bull sharks. Over the next several days, we set our longlines out to fish for them. A longline has a central mainline; at set intervals, a branch line with a hook is clipped to it, and connected to that is a float line to hold the main line up in the water column (see figure for more details). Long lines can stretch for miles, but ours was only 750ft long, a shortline if you will. We use circle hooks so the sharks don’t swallow them and extra-long branch lines so the sharks can swim around and get water moving over their gills once hooked. We want these animals as healthy as possible. Sadly, no sharks decided to test our gear that day, so we headed back to our island home.

Fieldwork starts early, so I headed down to our dock to cut bait and swatted away the flies in the still-dark morning. As the sun was just beginning to rise, we headed out to our sampling site. The Gulf was choppy, and our tiny craft skipped across the waves until we reached the sheltered waters of the river. We spooled out line and waited for a bite, not from mosquitos. Not five minutes after setting, the most dangerous creatures of the river reared their ugly heads. Speed boats ripped through the river, narrowly missing our lines, but the wake that followed their crafts twisted the line into tight knots. We didn’t have any fancy winches or pulleys, just elbow grease and baskets to coil our line, preferably as fast as possible to remove knots and get any sharks off. Hook after hook came up empty. We were constantly battling the current to stay with the line and out of the weeds that would clog our engine. The wake from boats only pushed our skiff and longline closer to the bank. On the fourth to last hook, the line shook as I grabbed it. My heart leaped at the possibility of a shark. As I pulled the line in I, saw the grey top, the flash of a white belly, and…whiskers. It was a white catfish (Ameirus catus). Our captured friend croaked a string of likely profane protests as I unhooked them. We continued to set our lines throughout the day and only found more of the same.

After a long day of fishing, we steered our craft into the Gulf and headed home. The onboard GPS was broken, and we had to rely on a nautical chart smartphone app. The app was slow to update, so frequent course corrections were needed, making for slow travel. A bad day in the field is still better than any day in the office. Still, after a year of waiting and nothing so far, I blamed myself for not having the magic foresight to find the sharks. Luckily, I have a patient partner who always reminds me to take some deep breaths and think rationally. Unfortunately, my calm didn’t last for long after arriving back at Seahorse. A tour boat full of camera-slinging passengers pulled up to our dock, and the guide seemed less than thrilled to see people there. The island is closed most of the year to the public to preserve the habitats and protect the wildlife, but people don’t always do what they are told.

After politely turning the tour group away, I began cleaning the gear as my fiancé headed up the hill for a well-earned shower. About 20 minutes later, I started up the hill, grateful for the breeze wicking away my sweat. My heart skipped a beat, and my spine went cold as I saw two men staring into the windows of the house. I shouted, and they took off to the back of the building. I sprinted after them but with a lead of several hundred feet, I had little hope of catching them. I gave chase nonetheless to make sure they left the island. Rounding the house, I headed down the winding path towards the island’s southern shoreline. Bursting through the thick branches onto the beach, I was immediately met by a teenage girl and her grandmother. I could see the men running down the beach towards a boat, but I stopped in front of the two women. They claimed the island was open, and they weren’t doing anything bad. I informed them that there were signs in the water surrounding the island saying restricted area. By now, the men were in their boat and moving off, so I politely asked the women to leave again and started the hike back up the hill. In the women’s defense, we are blessed with hundreds of millions of public lands in the US. Granting our citizens access to preserved wild places to recreate. But to quote a wise game warden, “Ignorance isn’t an excuse for breaking the law.” Once I got in the house, I hugged my freshly washed better half, who protested that I was getting fish blood on her. I had been so worried about her being scared, but it turned out she didn’t even know there were peeping toms.

After a couple of days of catfish, aggravating humans, patchy thunderstorms, and no sharks, we needed a fresh set of eyes on the problem. Our program director Dr. Naylor came out to lend his expertise. Gavin arrived just after lunch, and we all immediately started the hours-long commute to the sampling site. The forecast called for possible storms, so we would have to be quick. We scouted around, weaving in and out of narrow offshoots from the river, looking for promising spots. By the time we were done, the possible storms had become a reality and were coming right at us. We could not stay out in the Gulf with such a small craft during bad weather. The wind had picked up, and the waves were growing large. We couldn’t afford to go slow, so I pushed the throttle down. The following two hours were intense, to say the least. I was surfing the waves with the hull and zig-zagging to avoid being flipped by rogue swells. Gavin braced against the polling platform above the engine, and my fiancé clung to me on the floor of the boat while shouting navigation instructions over the wind. I guided us home safely but literally shaken just before dark.

In the morning, we headed to a fishing spot closer to home, following the guidance of the Island caretaker. While not the right location for our study, we could at least test our new gear and get an idea of what species were here. We laid out our line and began the 30-minute soak (wait) time. Running parallel, 500 ft from our line, was a row of connected crab pots. 15 minutes into the soak, a red and white speed boat roared along the coastline. The driver was swerving at high speed and turned towards us. He first ran over the crab pots dragging the line with him and then over ours. He continued into the islands swerving erratically, likely from a morning of drinking. We began pulling in the line, now weighed down by the tangled crab pots. We felt tugging around the halfway point and then saw a large splash at the end of the line. Gavin shouted, “Bet it’s a big bull!”. When we finally got to the spot, all that remained was the hooked severed head of an Atlantic sharpnose shark (Rhizoprionodon terraenovae). There had been a bull shark, but it was feeding off our line, not hooked. In the end, we got two live Atlantic sharpnose and one juvenile blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus). The damage to the lines ended up being minimal. A float was damaged, a branch line cut, and the mainline was cut but not severed. Despite this, our spirits were high from finally catching some sharks.

Gavin left that afternoon, and we headed back home to clean gear, untangle the line, and build replacements for the damaged sections. That night the storms returned, blowing open doors and slamming debris against the house at 2:30 A.M. Weather along the coast can change quickly and is often hard to predict. This storm had turned violent since I had checked the radar before bed. Worried about the boat and supplies, I grabbed my coat, boots, headlamp and charged down the hill in the dark. The wind was blowing so hard I could hear the howl through the trees and the rain was going sideways. I made it to the dock and grabbed some already blown gear off the ground and beach. The boat was secure, but I added an extra dock line to be sure. I made my way back up the hill; my pajama pants were soaked and chilling me, but I was anxious to check on my crew. She had gotten the doors secure and had made me a hot tea to ward off the damp chill. I did a once over of the house to check for leaks and fell back asleep before my head hit the bed.

After such an exciting night and the forecast calling for more storms, we decided to cut our last day short. We loaded up our gear and bid fair well to our private island home. The morning was cool from the midnight storm, and the sunrise light was making the water dance. This may not have been the most successful trip, but it was a welcome change of pace from months in isolation. Fieldwork in science is about adapting to the unexpected, this trip was no exception. After we loaded the truck and parked the boat trailer, I treated my partner to a fancy seafood lunch on the deck of a local restaurant. The storms wouldn’t be there for another hour, but strong winds buffeted us while we ate our grouper and chips. Not everyone has a significant other that would help them go catch sharks in the middle of nowhere. It’s hard, dirty work that’s not for everyone. I count myself blessed to be with someone so caring, giving, and patient. Thank you, Bee, for all your work.