Epidemic diseases ravaged both Indians and Spaniards through the seventeenth century.

Between 1614 and 1617 friars estimated that nearly half of the Timucua Indians died. Yellow fever became epidemic in 1649, killing Spaniards and Indians alike. A smallpox outbreak occurred in 1655, and killed all of the African Royal slaves, as well as large numbers of Spaniards and Indians. A measles epidemic struck in 1659.

Health care in St. Augustine was at best very primitive, and the hospital established in 1597 was described in 1605 as a “miserable hole”. There was a 6-bed ward attached to the church of La Soledad, but no doctors were in attendance. Physicians were only sporadically present in the town, and most were foreign captives, taken from shipwrecks.

The decrease in Indian populations from epidemics meant decreased food and labor sources in the hinterlands. Increased Spanish demands for Indian labor and foodstuffs contributed to several uprisings among the Florida Indians.

In 1597, the Guale Indians of the Georgia coast rebelled, there was a revolt in the Apalache province in 1647, and a major rebellion in the Western Timucua province in 1656. These events severely exacerbated the already tense conflicts between Crown authorities and the Franciscans.

As if disease and rebellion were not enough, the wood and thatch houses of St. Augustine suffered devastating hurricane damage in 1597, 1622, 1638 and 1674. Perhaps the worst disaster was the sacking of the town by the English pirate Robert Searles (a.k.a. John Davis) in 1668.

Searles and his men, sailing in a captured Spanish ship, attacked a surprised St. Augustine at midnight. As the town residents fled to the woods, the pirates killed 60 people, took many well-to do young women for ransom, and completely sacked the town. They did not burn it, however, causing the Spaniards to fear that Searles was planning to return and capture the colony.

Artifacts

Images

People

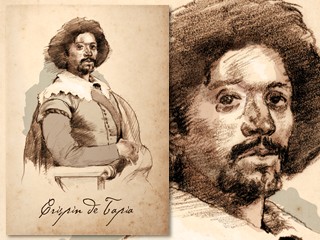

Crispin de Tapia

Corporal de Tapia was a free person of color during the latter part of the seventeenth century. He was a Corporal squad leader in the 48-man free black and mulatto militia formed in 1673, which was an important unit in defending St. Augustine from pirates. He also operated a “teinda de pulperia”—a general goods shop—in St. Augustine.

Pedro Piques

Piques was a French surgeon who assumed the post of the regimental surgeon in 1666. On the basis of gossip passed to Governor Francisco de la Guerra y de la Vega from one of his several mistresses, the Governor slapped Piquet, refused to pay him, and sent him away from St. Augustine. Piques’ ship was captured between St. Augustine and Havana by none other than Robert Searles, to whom the angry and revenge-seeking Piquet provided all the information necessary to attack St. Augustine. Searles promptly did so.

Estefanía de Cigarroa

Estefanía was the daughter of regimental Major Salvador de Cigarroa. She was in St. Augustine the night of the 1686 Searles raid, and ran into the street carrying her younger sister. One of the pirates shot at them, killing the smaller child and wounding Estefanía in the breast. It is not known if Estefanía was one of the well-to-do young ladies taken for ransom, but as an officer’s daughter she would have been both an eligible ransom candidate and an eligible bride in St. Augustine.

Bernardo Nieto de Carvajal

Bernardo Nieto de Carvajal came to St. Augustine as a soldier in 1680, and he led the successful battle against the French pirate Grammont when the pirate forces marched on St. Augustine in 1683. Perhaps because of this, he did not share the belief held widely by the townspeople of St. Augustine that the pirates were repelled by the miraculous properties of the Christ image in the church of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad. He unwisely expressed his views during a visit to the house of Ana Ruíz, a widow with four daughters, aged 18-25. When his hostesses marveled at the wondrous intervention of the Holy Christ image, Bernardo replied, “What Holy Christ?”, and asserted that it was the actions of his soldiers that had turned away the pirates. He further suggested that they try putting the Holy Christ on the beach and let him defend the city alone. The shocked widow Ruíz reported Carvajal to St. Augustine’s minister for the Holy Inquisition, who arrested and imprisoned Bernardo for blasphemy. He was sent to face the Inquisitorial Tribunal in Cartagena, which found him guilty of “heretical blasphemy”. Rather than being sent to prison, however, the Tribunal rebuked him and sent him back to serve in St. Augustine.