At the middle of the seventeenth century, St. Augustine’s population was only between about 500 and 600 people. By the end of that century, it had risen to more than 1,400, and by the time the Spaniards evacuated St. Augustine in 1763 there were more than 3,000 residents.

This steady growth came about through major increases in the number of soldiers in the garrison, the arrival of groups of convicts and laborers sent to St. Augustine to work on the fortifications, and to large refugee populations of Indians and Africans who began to enter the town after 1680.

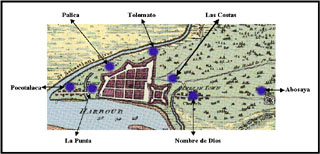

The Indian population of the St. Augustine presidio was counted at 90 in 1675. Fifteen years later it had risen to 225, and grew steadily until 1728 when a census recorded 1,350 Indians in refugee villages around the town. These included Timucua, Guale, Yamassee, Apalache, Jororo and other groups seeking refuge from English slave raids. Not all were Christians, but their presence in the settlement (like that of the Africans) contributed to the diversity and exchange of cultural elements that was a hallmark of eighteenth century St. Augustine.

The diversity of St. Augustine’s population became even more pronounced between 1757 and 1760, when 97 families of farmers from the Canary Islands immigrated to Florida, where they established farms and small enclaves north of the town. Although soldiers from the Canary Islands had been stationed in St. Augustine throughout the century and were considered peninsulares, the newcomers were relegated to peón status and remained outside of St. Augustine, much to their peril from English and Indian raids.

Artifacts

Images

People

María Magdalena Chrisístomo-Balthazar

María Magdalena’s mother, María Luisa Balthazar, was a Mocama Timucua Indian from the village of Palica, and her father, Juan Chrisístomo, was a Caribali African slave living in St. Augustine. María Magdalena and her sister Josepha Candelaria were born in their mother’s village, and were free. María Magdalena was married three times, first to Juan Margarita, who was thought to have been an Indian. In 1743 she married Pablo Prezilla, a free mulatto from Venezuela, and in 1745 she wed her third husband, Phelipe Gutiéres, a white criollo. María’s sister Josepha married in 1747 to an Indian of La Punta, Juan Manuel Manressa, and went to live with him there at the south end of the Spanish town. After María Magdalena’s and Josepha’s mother died in 1744, their widowed father Juan married Antonia, an African woman who was, like himself, a Carabali and a slave. They were married in January of 1744, the same month in which their first child was born. They subsequently had several other children. By 1750 Juan had gained his freedom and was a member of the Mose regiment, but Antonia and the children remained enslaved, living in St. Augustine. (Landers 99:58).

The Ribera-de la Cruz Family

Pedro Ribera and María de la Cruz were Guale Indians, and Pedro, at least, had been born in the village of Tolomato. They lived in St. Augustine, where Pedro was a member of the cavalry company, and María may have been a midwife. The marriages of their four children illustrate the changing social conditions and increasing social diversity and fluidity in St. Augustine of the mi-eighteenth century. Their daughter, Ana Lucía, married a peninsulare soldier from southern Spain. One of their sons, Juan, married a woman from the Canary Islands, recently arrived as part of that immigrant group. Two other sons married white criolla women: Francisco Xávier to a first generation criolla, and Antonio to a well-placed criolla. She was, in fact, a first cousin to the Governor’s wife.