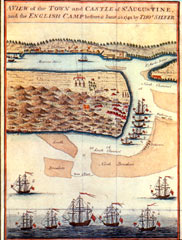

Military skirmishes and encounters between Spanish and English forces (and their respective Indian allies) over control of the area between Charleston and St. Augustine began almost as soon as Charleston was established in 1670, and they escalated dramatically through the eighteenth century.

Most of the remaining frontier missions, and St. Augustine itself, were burned down during the sieges of Carolina governor James Moore in 1702 and 1704. By the end of first decade of the new century, Spanish activity in East Florida was restricted to St. Augustine.

One of the most aggravating aspects of the conflict for the English colonists was the role taken by their African slaves. Africans who escaped from English plantations were given sanctuary by the Spaniards in Florida, to the outrage of their former owners.

The first African refugees arrived in 1686, and by 1738 their numbers were sufficient to form a free black militia, settlement and fort a few miles north of St. Augustine, known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose. They represented a first line of defense for St. Augustine against English raiders.

For more information, please visit the Florida Museum’s Historical Archaeology website.

Artifacts

Images

People

Francisco Menéndez

Francisco Menéndez was a Mandinga born in West Africa in 1704. He was captured and sold into slavery to an English planter in the Carolinas sometime before 1720. He escaped, and fought with the Yamassee Indians against the English for several years. In 1728 Menéndez arrived in Florida in the company of Yamassee Indians, but despite the King of Spain’s 1693 proclamation “giving liberty to all,” Menéndez and 30 other escaped Africans were enslaved. Although a slave at the time Francisco became the Captain of the town’s black militia, and petitioned the crown for his and his compatriot’s freedom. This was granted in 1738, and Menéndez became the Captain of the Mose militia and the governor of the newly-found settlement of Mose, a position he held until his departure from Florida in 1763. During the interlude between the destruction of Mose by Oglethorpe in 1740 and its rebuilding in 1752, Menéndez hired on as a privateer on Spanish corsair ships. He was captured and tortured by the English, but escaped to write an account of his ordeal, and resume his leadership of the Mose community.

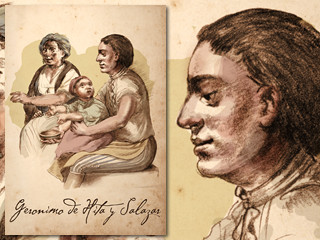

Gerónimo De Hita y Salazar

Gerónimo was born into a prominent St. Augustine criollo family in 1706. He was the son of Adjutant Don Pedro de Hita Salazar and one of thirty-two grandchildren of the peninsulare Governor Pablo de Hita y Salazar, who had settled in St. Augustine when his term ended in 1680. By the time Gerónimo reached adulthood, the rules against admitting criollos to the St. Augustine garrison had relaxed, and the deteriorating military situation required more men. Gerónimo was admitted to the garrison in 1734 at the age of 28 as a cavalryman ( a more prestigious and better-paid branch of the service than those of infantry or artillery). Two years later, he married a young criolla widow, Juana de Avero, six days after the birth of their first child, Eugónia Basilia. Juana and Gerónimo had three more daughters and one son before they left for Cuba in 1763. Gerónimo’s was not a career of distinction. After 18 years of service, he remained a private, although he was, after the mid-1750’s, commandant of the black garrison at Fort Mose.

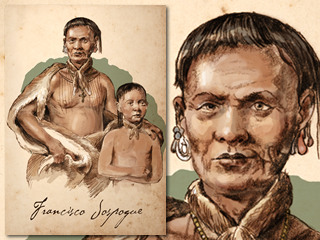

Francisco Jospogue

Chief Francisco Jospogue was a Guale Indian, born shortly before 1670 near St. Catherine’s Island, in Georgia. He was chief of his village when English and Yamassee attacks forced the Christian Guale to migrate to St. Augustine, where his people settled at a mission town called Nombre de Dios Chiquito. In 1715, his wife and four children were captured by Yamassee Indians during one of the many English and Yamassee raids on the Indians of St. Augustine. Three times the English offered to return Chief Francisco’s family to him on the condition that he ally himself with the English and renounced Catholicism. Three times he refused, and his family was separated and sold into slavery. By 1717 Francisco was the leader of the village of Nuestra Señora de Candelaria, a village of heathen Yamassee Indian refugees, and before 1728, he remarried. His wife, Agustina Pérez was a mestiza, and gave birth to their son Miguel in 1728. By 1734, Francisco and Agustina had moved into town, living in a tabby house on St. George street. (Parker diss 57-59).